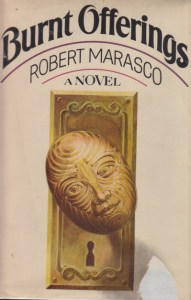

Summer vacation—or at least what used to be known as summer vacation—is winding down. Unlike most years when the season is marked by a carefree sense of time off and travel, many of us spent it locked down while the Republicans have used revisionist history on the pandemic, claiming against all facts that America handled it best. Is it any wonder some of us turned to horror to cope? My latest piece in Horror Homeroom has just appeared (you can read it here). It’s on the movie Burnt Offerings. The movie is set in summer with its denouement coming just as vacation time ends. I’ve written about it here before, so what I’d like to mull over just now is transitions. The end of summer is traditionally when minds turn to hauntings.

Doing the various household repairs that summer affords the time and weather for, I was recently masked up and in Lowe’s. Although it was only mid-August at the time, Halloween decorations were prominent. Since this pandemic—which the GOP claims isn’t really happening—has tanked the economy, many are hoping that Halloween spending (which has been growing for years) will help. My own guess is that plague doctor costumes will be popular this year. Unlike the Christmas decorations that we’ll see beginning to appear in October (for we go from spending holiday to spending holiday) I don’t mind seeing Halloween baubles early. There is a melancholy feel about the coming harvest and the months of chill and darkness that come with it. Burnt Offerings isn’t the greatest horror film, but it captures transitions well. (That’s not the focus of the Horror Homeroom piece.)

Many of us are wondering how it will all unfold. Some schools have already opened only to close a week or two later. Those in Republican districts are sacrificing their children (this is the point of the Burnt Offerings piece) in order to pretend that 45’s fantasy land is the reality. The wheels of the capitalist economy have always been greased with the blood of workers. (Is it any wonder I watch horror?) As I step outside for my morning jog I catch a whiff of September in the air, for each season has its own distinct scent. I also know that until the situation improves it will likely be the last I’ll be outdoors for the day. It has been a summer of being cooped up and, thankfully, we’ve had movies like Midsommar and Burnt Offerings to help us get through.