It was in Maine. In 1987. I can’t remember how Paul and I found this place to camp. I don’t remember making reservations, but we drove along in his 1968 VW Beetle, unpacked a tent along a rutted logging road, and set up camp for the night. We were there to try to find moose. In the middle of the night we were awakened by howling in the woods. We were many miles from any other humans and nobody knew where we were. Were there wolves in these woods? Paul turned to me. “Wolves don’t attack people, do they?” he asked. I said no. He pulled out a very large knife. “I was in the civil air patrol,” he explained. “You know what to do with this, right? If a wolf bites your arm, cut your arm off and run away.” Not the best advice. As we drifted off to sleep we were awoken again by furious sniffing outside the tent. The next morning we saw no moose but found tracks all around our temporary home. We convinced ourselves they were wolf tracks. They were actually tracks of coyotes.

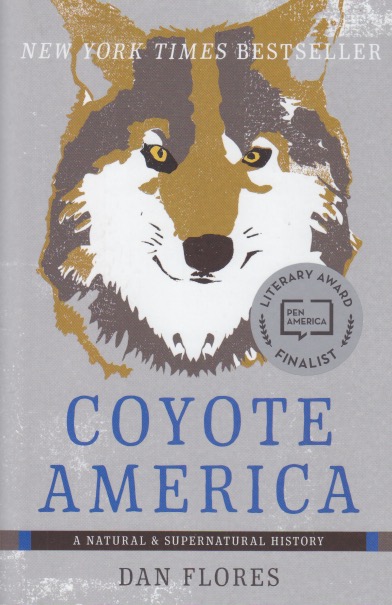

Most people in America have a coyote story to tell. I can’t recall how I learned about Dan Flores’ Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History. I’ve always been drawn to nature writing, but it was probably the “supernatural” that caught my attention. This is a fascinating book with a rollercoaster ride through emotional responses. Flores makes the case that Coyote was the first god of America. Indian mythology is full of this character and his antics. But the heart of the book focuses on the many decades of efforts—still ongoing—of the government to eradicate coyotes. Millions of them have been killed for spurious reasons, largely because the government pays attention to ranchers who pay a lot of money to be minded. Coyotes naturally find their balance in nature, which we insist on disrupting. One of their survival strategies has been to move east. Even moving into cities.

I’ve heard coyotes in Wisconsin, and I saw at least one while out jogging in the early mornings there. Since moving east I’ve not spotted any, but they are, I know, here. I’m largely on the side of nature, but the first ever documented adult human wolf fatality took place in another place I’ve camped, Cape Breton Highlands National Park in Nova Scotia, in 2009. Reading this made my human pride rear up—we don’t face predators well. The book goes on to touch on how I, and many others my age, learned of coyotes—through Wile E. in animated form. This book is difficult to read in many parts, but it is an absolutely mesmerizing journey through many lenses of what it means to be American. Whether you’re canine, or human.