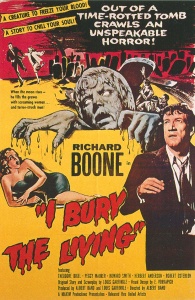

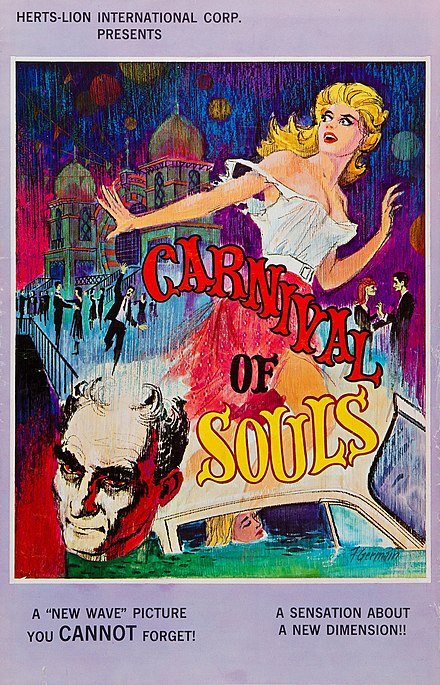

I don’t always believe the statistics. Numerically, the number of horror films—depending on how the term is defined—declined into men (and sometimes women) in rubbery suits in the 1950s. Indeed, it’s often opined that had not Hammer joined the horror business in the mid fifties that the genre born only twenty-something years earlier might’ve died out. There seem to have been some good horror films made then, though, even if overlooked because of their B status. A friend recently directed me to I Bury the Living, after reading my post about Carnival of Souls. I have to confess to having never heard of I Bury the Living. (Stephen King mentions it in Danse Macabre.) Produced as a B movie it was itself buried among the various other efforts of the late fifties. It’s not a bad movie, however. In fact, it’s better than the title might lead you to believe.

The plot is something of a period piece—a well-respected department store supports a cemetery committee for Immortal Hills, the town’s graveyard. Robert’s turn as chairman of the committee arises and he tries unsuccessfully to get out of the duty. The caretaker, Andy, doesn’t want to retire, but he’s aging out. The movie, however, revolves around the map. The sold plots are marked with white pins while the plots already occupied have black. When Robert accidentally puts black pins into newly purchased plots and the couple dies, he believes he’s cursed with an ability to kill those he black pins. He substitutes a black pin for a white one at random. The person dies. In all, seven people succumb. Convinced he’s murdered them, Robert decides to bring them back to life but putting the white pins back. Only at this point does Andy confess that he’s been killing the victims in retaliation for being forcefully retired.

The ending is a little weak, but the psychological tension as it builds up is believable. One critic compared it to an extended episode of The Twilight Zone, a comparison that has also been made for Carnival of Souls. I would concur with that observation. Although Twilight Zone wouldn’t air for another year, that kind of unsettling tale was already in the air. No zombies appear, but the palpable belief that they might is what really makes the horror work in this instance. The first half is an eerie story, but when Robert sticks in that first white pin a shift takes place. Of course, modern viewers have been primed by Night of the Living Dead, so we know the possibilities. Perhaps the power of Night gives life to older movies. After all, anything can happen in the Twilight Zone.