Like religion and horror, humor and horror can also get along well. As an aesthetic, it’s not for everyone, but Grady Hendrix does it well. It took some convincing for me to read The Final Girl Support Group. I’d read one of Hendrix’s nonfiction books and was impressed, and that led me to his fiction. It also demonstrates how an academic might actually be able to make a difference. As you might guess, the novel features “final girls” from several fictional events, made into fictional movies, who get together for therapy. It’s a funny idea and yet it’s not. Hendrix clearly wants women to be treated fairly, but he’s also clearly a horror fan. It’s sometimes a tricky balance to hold. He does it pretty well in this novel.

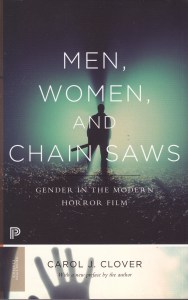

The idea of a “final girl” comes from Carol Clover’s crossover academic book, Men, Women and Chain Saws. This is the book that introduced the concept to the world. As with most analytic concepts it’s only an approximation. Clover noted the way that, in slasher films, the only survivor tends to be the virginal girl who doesn’t join in substance abuse. Since the slasher genre is usually first credited to John Carpenter’s Halloween (Hendrix suggests in his acknowledgments that it’s Psycho), I’ve always wondered because Laurie Strode does take a toke in the car and we’re not really told much about her dating life. I’m not a big fan of sequels, so maybe I’m missing something. In any case, slashers have never been my favorites, and as sexist as it might sound, Poe’s observation about threats to beautiful women is something the “final girl” relies heavily upon.

The novel itself is pretty gripping. I’m not going to put any spoilers here. I was reluctant to read it but I’m glad that I did. It’s classed as “horror” because of the theme but there’s definitely a lot of literary finesse as well. It’s the kind of thing that doesn’t really seem to be deep, but upon reflection, it has more to say than you think it does. The resolution of the novel is messy. I suppose that’s one thing that makes it literary. The characterization is amazing well done. I had trouble keeping track of the back stories of all the final girls but that’s part of the fun. While there are definitely horror moments, Hendrix never lets you forget that you are supposed to be laughing too. It’s a fine balance and he manages to hold it together throughout while giving agency to final girls.