We’re accustomed to religions being written out. Indeed, many world religions have sacred texts from the Avestas to Dianetics. Some ancient cultures, however, didn’t have written traditions and when they disappeared, as all cultures eventually do, their religion became nearly impossible to understand, or reconstruct. Miranda Green has tried to provide, in written form, a summation of her understanding of The Gods of the Celts. Celtic mythology, interestingly, had long ago caught the attention of New Religious Movements, as well as the New Age movement. Much of the Wiccan calendar is based on Celtic religion and many New Age practices trace their roots to the ideas of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales lost to the mists of time. What we actually do know about these cultures is about as fascinating as what’s been reconstructed.

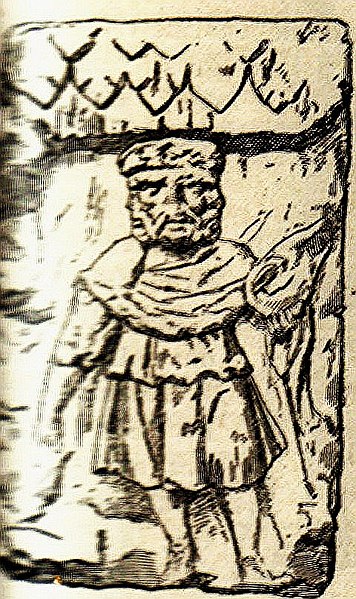

Green’s study shows us a religion that grew out of profound respect for nature as well as human prowess at fighting. (The “fighting Irish,” indeed may touch on an historical pulse.) Celtic gods reflected a large swath of thinking throughout western, and parts of eastern, Europe. Their names may be less familiar to us, and some may well have been lost to the vicissitudes of time, but there was a vibrant devotion to them that went as far as human sacrifice. We know that it occurred, but it probably wasn’t frequent. Although polytheistic, Celts were moral in their own understanding of their world. Morals tend to come from human understanding of their place in a world they didn’t create. How do you live in somebody else’s property?

Unlike the more literate Greeks, or even the Semitic religions on which they drew for their stories, we have no narrative Celtic mythology. We have fragments and glimpses. Nobody had a recorder while sitting around the fire, recounting the activities of the gods. Later, sources such as the Mabinogion were written down, which surely held some memories of such fireside tales. The originals, however, we’ll probably never have. Such is the way of conquered peoples. What the Romans started the Christians finished. We’re left with some deities, such as Brigit, made into saints, but their stories forgotten and not originally written down. Our time looking back isn’t ill-spent. It teaches us who we are and guides who we might become. Our own violent politicians, threatening to murder those who are different, clearly have learned nothing from history, ancient or modern.