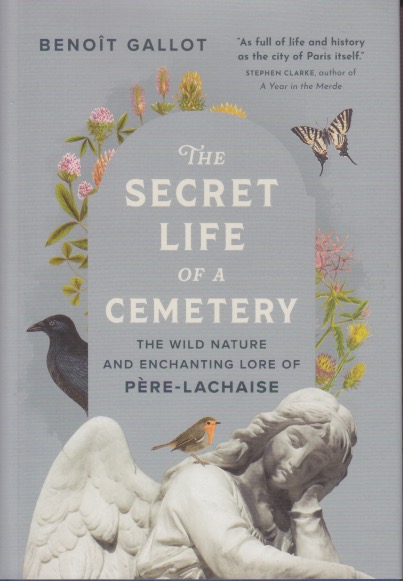

I have to confess that I really didn’t know about Père-Lachaise Cemetery before this book. I knew that Jim Morrison was buried in Paris, but I’d never really paid attention to where. My wife picked up Benoît Gallot’s The Secret Life of a Cemetery: The Wild Nature and Enchanting Lore of Père-Lachaise and we decided to read it together. It seems likely that Père-Lachaise is the world’s most famous cemetery. This little memoir by the current curator of the cemetery is a delightful read. It is reflective and sensitive (and spawned by the attention the author’s social media was getting, so hey, help me recruit some fans!). Gallot began posting pictures of wild animals that he snapped in the course of his work and Parisians, and others, were fascinated to learn about wild animals at home in the capital of France. This book reflects on the animals, plants, and people of the graveyard.

I enjoyed this book, but one aspect gave me pause. Gallot notes that the cemetery doesn’t permit jogging. Perhaps this is a cultural thing, but cemeteries have been some of my favorite jogging spots. I mean no disrespect by it. Cemeteries are peaceful and have very little traffic (one of a jogger’s concerns). I’ve never found people walking their dogs (another jogger issue) in cemeteries. I can see how mourners might not want to see someone taking their exercise near the grave of a departed family member, but a jog is simply a fast walk. And we are, as a species, part of nature.

Many famous people are buried in Père-Lachaise. I visit cemeteries to find famous people’s burial places. Indeed, that’s what I tended to post on my Instagram site, but I found no followers. We had visited Highgate Cemetery in London—another famous burial ground—and discovered many familiar names there. Perhaps to Anglophones, Highgate is more famous than Père-Lachaise. But even Highgate would’ve been off my radar had it not been for the Highgate Vampire incident that I’ve written about before. Gallot, who lives in the cemetery, is skeptical of ghosts in Père-Lachaise, although he’s well aware that the stories are told. This brief book is contemplative autumnal reading. There are several black-and-white photos of animals among the graves. They are the living among the dead, and an appropriate symbol that life goes on. If you’re looking for a place to reflect on mortality and you want to learn about cemetery life, this may be the book for you.

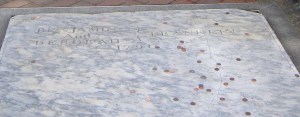

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.