One of the concomitants of spending time with religion is a non-morbid fixation on death. As a college student I was surprised to learn that other people my age did not think about death nearly every day. Perhaps with a typical college student’s obsession with the other end of the life cycle this is only natural. Ever since I was a child, however, I felt frustrated by the lack of permanence that characterized all of the striving involved with life. We work very hard and then we die. I suppose that is one of the reasons religion appealed so strongly to me—it had an answer to this dilemma. Science, as I began to experience it about the same time, suggested a radically different conclusion: we have no souls, and so it is best to accept the fact that death is the end and get on with life. No wonder Ecclesiastes has always been my favorite book of the Bible.

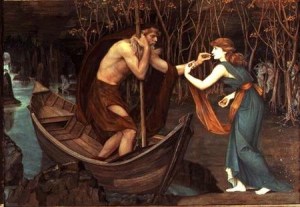

While reading about–shhh!–death recently, I came across an interesting tidbit. Pope Pius IX was buried with a coin. I’ve read that even John Paul II was buried with coinage, but I’ve not been able to find credible sources on that. What is fascinating about this practice is that no matter how it is vested, burial with money is a form of Charon’s obol. With movies like Clash of the Titans, many modern people are aware of the need to pay Charon to cross the River Styx. (Back in the radical days of traditional education just about everyone would’ve learned this in the course of studying the classics. In any case…) The gifting of the dead with money represents the survival of a pagan custom that likely stretches back well before ancient Greece. Even before money was invented people buried the dead with goods that the living would never be able to use again. They may not have considered this payment to a ferryman, but the principle is the same.

This idea has a strong grip on our psyches. Not one of my favorite movies, I have watched Ghostship a time or two. What initially brought me to the movie was the fact that it is a horror-movie built around the character of Charon. The mysterious stranger who lures the crew of the Arctic Warrior onto the Antonia Graza laden with gold is named Ferriman. The salvage crew quickly forget the tons and tons of metal that they came for in exchange for the a few dozen bars of gold. Of course, a sole survivor lives to tell the tale. The thing about Charon’s obol is that once he is paid, death is inevitable. Thus death and money are inextricably twined like earbuds carelessly tossed into a backpack. It seems that no matter how you measure it, the only winner is Charon. Maybe the Greeks have something to teach us yet.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

The specific form of penny offerings seems to go back to Benjamin Franklin’s burial, at least in America. A few years back while in Philadelphia, I saw for myself that people still leave pennies on Franklin’s grave in Christ Church Cemetery.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.

I recalled having seen stones on tombs outside Jerusalem some years back, and I even had a student bring me a stone from Israel to keep as long as I promised to put it on her grave after she died. This practice in its recent form is associated with Judaism, but again, it has ancient roots. The building of cairns, or piles of stones, is often associated with the Celts or the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles. On our many wandering through the highlands and islands we saw several Neolithic examples in Scotland, particularly in the Orkney Islands. The practice of putting stones atop the dead also goes back to ancient times. One plausible suggestion is that it was intended to keep the dead in their graves. A more prosaic conclusion is that digging deep holes takes more work than hauling over a pile of rocks.