God is great, despite what Christopher Hitchens wrote, at least, that is, if you want to save 15% without having to talk to a gecko. According to Mulder’s World—I want to believe that what I find on this site is true, but often I find myself feeling more like Scully—Mary’ Gourmet diner in Winston-Salem, North Carolina gives a grace discount. Well, perhaps this is believable. Praying in public has a long pedigree. This past Corpus Christi as I was driving back into town after a day out, I saw a procession walking down the street a few blocks from the local Catholic Church. Vested and carrying a monstrance with a humeral veil, the priest led the faithful out in public for a little recognized festival many suppose to be named after a city in Texas. Actually, I was an acolyte for Corpus Christi one year at the Church of the Advent in Boston. The well-heeled of Beacon Hill, however, knew to expect us out on the genteel streets. Private prayer in public, however, is something quite different.

As a very religious teen, I often went to United Methodist Youth events with the other faithful young. We would stop into restaurants on our long drives and make a show of praying amid the heathen. Some of us (not me, I assure you) even left Chick tracts instead of tips. If we’d ever ventured into Dixie, we might have had a discount. The problem with offering a praying in public discount is that it is impossible to tell if such shows are sincere. I have sat through many such episodes, wondering about Jesus’ statement “But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly.” Well, that was only the Sermon on the Mount. Here we’re talking fifteen percent! “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.” This gecko winks.

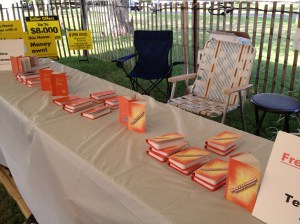

Public displays of piety are not uncommon. I spent yesterday at the local County 4-H Fair on a rare day off of work. The Gideons, as always, were there handing out New Testaments. Let your light so shine—they are bright orange. Religious freedom ensures that prayer in public is kosher, as is agnosticism in public. Who is harmed by a public prayer? In that diner, who is made uncomfortable? Sometimes the innocuous act of kindness is a sign of mature morality. How many times—isn’t it nearly always?—does that car cutting you off in traffic have a Jesus fish plastered to the back? “I drive my car,” Daniel Amos sings, “it is a witness.” What you truly believe shows up when you’re behind the wheel more than when you’re behind the napkin. The truth may be out there after all. In the meanwhile, my tip’s on the table.

Public displays of piety are not uncommon. I spent yesterday at the local County 4-H Fair on a rare day off of work. The Gideons, as always, were there handing out New Testaments. Let your light so shine—they are bright orange. Religious freedom ensures that prayer in public is kosher, as is agnosticism in public. Who is harmed by a public prayer? In that diner, who is made uncomfortable? Sometimes the innocuous act of kindness is a sign of mature morality. How many times—isn’t it nearly always?—does that car cutting you off in traffic have a Jesus fish plastered to the back? “I drive my car,” Daniel Amos sings, “it is a witness.” What you truly believe shows up when you’re behind the wheel more than when you’re behind the napkin. The truth may be out there after all. In the meanwhile, my tip’s on the table.