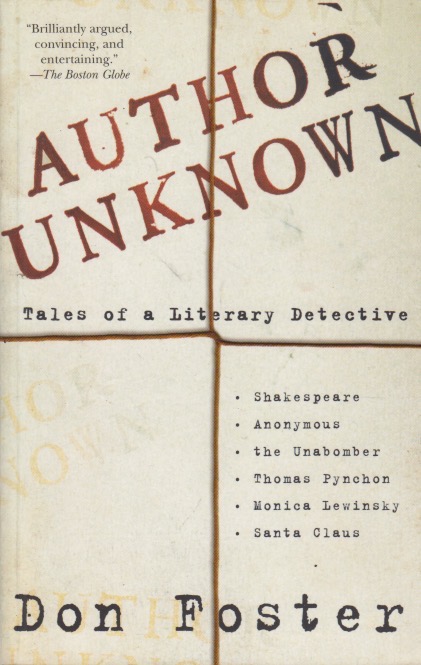

Ratiocination. Detection. There’s something compelling about that clear, crystalline logic that leads to solid conclusions. I was floored by Don Foster’s Author Unknown: Tales of a Literary Detective. I found the book by following up a reference to “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” aka “’Twas the Night before Christmas.” Like most Americans I credited the poem to Clement Clarke Moore, but he did not, in fact, write it. If you trust anyone with literary detection, it should be Don Foster. Although this cleverly written book is not an apologia for the author’s personal accomplishments, it nevertheless builds trust in his methods and his sense. It begins as he discovers an unacknowledged text was written by Shakespeare. The evidence is carefully laid out, and is convincing. Then others began to ask him to “prove” who wrote other pieces. It’s quite a ride.

While Foster takes great care not to claim the ideas as his own, he’s nevertheless drawn into the case of the Unabomber, and Monica Lewinsky, and Thomas Pynchon. His methods of ratiocination demonstrate repeatedly what he explains in his excellent introduction—our writing is every bit as indicative as our DNA. With an adequate writing sample size, a piece with an unknown or disputed author can, with a great degree of probability, be attributed to the correct author. You don’t even need to know of the cases to find the outcomes fascinating. And those who disagree, being human, are simply not convinced by his conclusions. They’ve already made up their minds. In this regard the case of Wanda Tinasky (I’d never heard of her) is utterly compelling.

The Santa Claus chapter, the final one in the book, is a real pay-off. Henry Livingston Jr., of Poughkeepsie, wrote the famous poem that defined Santa Claus as we know him. Considering Christmas’ importance in our capitalistic society, this attribution is an important one. Clement Clarke Moore was a very wealthy professor of Bible at the newly formed General Seminary. Foster demonstrates probable cause in his claiming, and keeping alive, the mythology that he wrote the famous poem. The way that this chapter is laid out and presented is especially witty. Those interested in getting at the truth behind who wrote what will find this a page-turner. Although he wasn’t seeking out the attention that came (most of us, as academics, are surprised when anyone show any interest at all in what we write) Foster has given the world a real gift in this book. It reminded me once again why research is the most intriguing thing on earth. And learning can be like reading a good mystery.