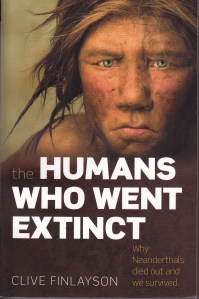

Envy is not a word I would use to describe how I feel about those trying to piece together the earliest stages of humanity. Evolution, naturally, is a given. Once beyond that, however, the landscape gets dicey. Clive Finlayson is an author I don’t envy. I just finished his The Improbable Primate: How Water Shaped Human Evolution, and it felt like he had to put this immense puzzle together while missing about nine-tenths of the pieces. Early human fossils are rare and it doesn’t take much to throw a laboriously constructed scenario into yesterday’s mistaken hypothesis bin. The central premise of the book, as stated already in the subtitle—human evolution followed water—seems about as firm as any idea. We need water daily and our bodies evolved to help find it efficiently. It’s a fascinating story. Along the way I learned that much of what I’d previously learned about ancient human development was probably wrong. I’m only a casual evolutionist.

Envy is not a word I would use to describe how I feel about those trying to piece together the earliest stages of humanity. Evolution, naturally, is a given. Once beyond that, however, the landscape gets dicey. Clive Finlayson is an author I don’t envy. I just finished his The Improbable Primate: How Water Shaped Human Evolution, and it felt like he had to put this immense puzzle together while missing about nine-tenths of the pieces. Early human fossils are rare and it doesn’t take much to throw a laboriously constructed scenario into yesterday’s mistaken hypothesis bin. The central premise of the book, as stated already in the subtitle—human evolution followed water—seems about as firm as any idea. We need water daily and our bodies evolved to help find it efficiently. It’s a fascinating story. Along the way I learned that much of what I’d previously learned about ancient human development was probably wrong. I’m only a casual evolutionist.

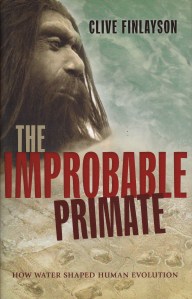

Finlayson suggests—and not all biologists would agree with him—that all humans living on earth at any one time (with one possible exception) were of the same species. That is to say, the model I grew up with of separate species (Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon were the usual suspects) duking it out over scarce resources doesn’t match growing evidence very well. We Homo sapiens seem to share some Neanderthal DNA and that paints a somewhat more romantic encounter between the species than the violent one I learned. The same goes for other human ancestors, according to this little book. Our first instinct may not be to kill the stranger. We may have lived apart for a few thousand years, but when populations come back together they “share genes,” if you get my drift. This still happens, of course. The difference is today we’ve become politicized and entitled. We don’t want people not from around here to share our stuff.

Part of that is natural, I suppose. Finlayson points out that the feeling of belonging in natal territory is something we share with other primates. We feel that we belong where we’re born. That seems to me a difficult thing to quantify, but I feel it nevertheless every time I venture back to my hometown. It just feels right. Not that we can’t adjust to elsewhere, but our nature rewards us, in some measure, when we come home. This is a wide-ranging study for such a small book. I don’t envy all the meticulous jigsaw staring without a box-top that students of human origins must do, but the results are still quite interesting. Even if the picture, when enough pieces are finally found, ends up being something different than we thought it was.