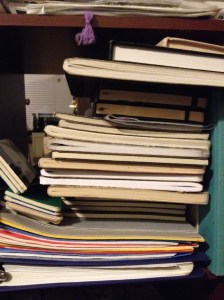

My wife is a saint. She doesn’t throw away the little scraps of paper on which I write notes to myself. They’re everywhere. And this even though I carry around a notebook to capture ideas. Sometimes I left it in the pocket of another pair of pants, or on the bedside table. And I need to write something down. Soon the scrap is filled with vital info (at the time) and eventually gets mislaid. When it’s found I need to go over it line by line to see if something remains crucial or if it was just prosaic (get oil change, set up eye doctor appointment, etc.). You see, ideas can strike at any time. I keep a commonplace book inside the door in case they do when I’m out jogging. I now keep a separate notebook on the bedside table in case something occurs as I’m falling asleep. And, of course, I keep my little zibaldone with me (when I’m wearing the right pants).

Those who believe electronics will save us suggest putting everything in a notes app. The problem is that I have several. I do most of my initial writing in Scrivener. When it’s time to share either with a publisher or a colleague, I convert it to Pages, and then to Word. But my devices also have Notes, which I can see synced on my phone. That makes it handy for shopping lists and such. Then there’s also Text Edit, which I use for rtf documents. Where an idea gets saved depends on which app I’m using at the moment. More scraps of paper, virtually. I need to write it down so I remember what’s where.

All of this led to a rather embarrassing situation the other day. As usual, I’m at work on another book. Since writing about horror isn’t something I was trained to do, I have to do quite a bit of bibliography building along the way. This is the kind of thing you learn in higher education, so no worries. The thing is I had started a bibliography in one app and began writing the book in another. I’d very nearly finished a draft of the book when I just happened to scroll through the folder where my former bibliography was kept. I was stunned to learn I’d already done this work since I didn’t remember recording this at all. I suppose the solution would be to record all my thoughts. But that would be too dangerous. And besides, when would I have time to review them all? I guess I still prefer scraps of paper, even if they’re sometimes electronic.