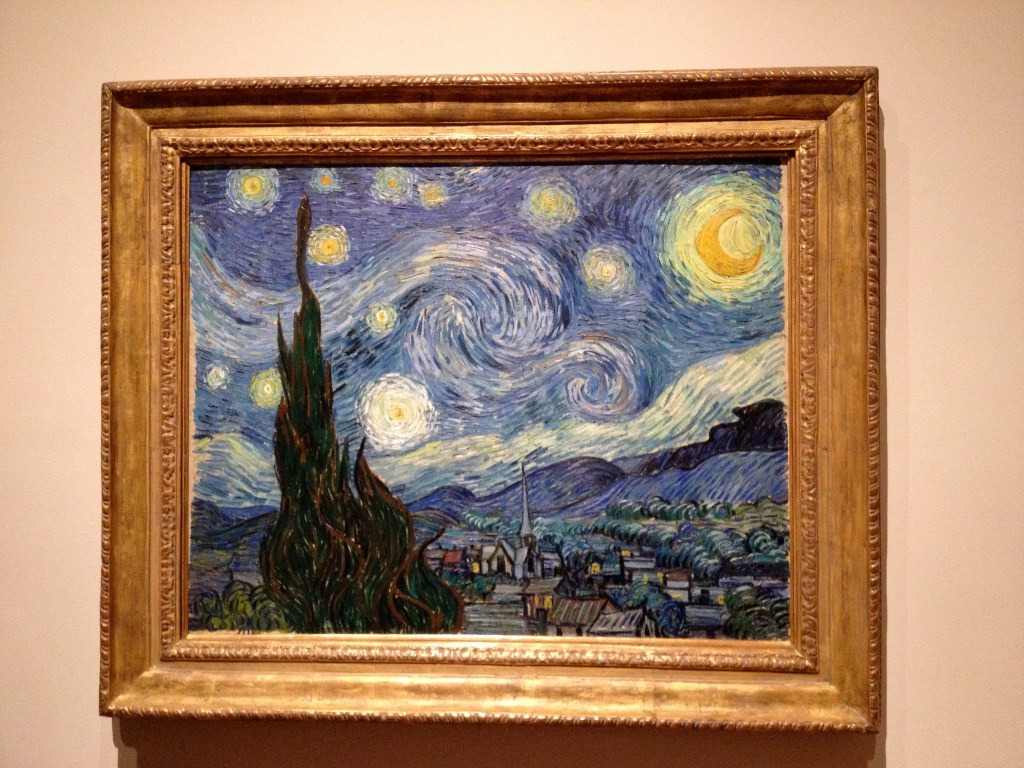

Few things glaze the eyes of others like somebody else’s genealogy. That’s not what this is, so unglaze those peepers! As with most of my posts, there is reflection here and that contemplation applies to just about everyone. We don’t know our parents very well. It’s only been when trying to connect the dots for my progenitors that I came to realize just how poverty-stricken that knowledge is. I could (and did) talk to my mother frequently, until recent days, but even to her my father was a mystery. I knew he was in the military for at least six years, so I filed a military records request with the National Archives. You can do this if you’re next-of-kin. That’s when I learned of the National Personnel Records Center fire of 1973 when at least 16 million records were destroyed.

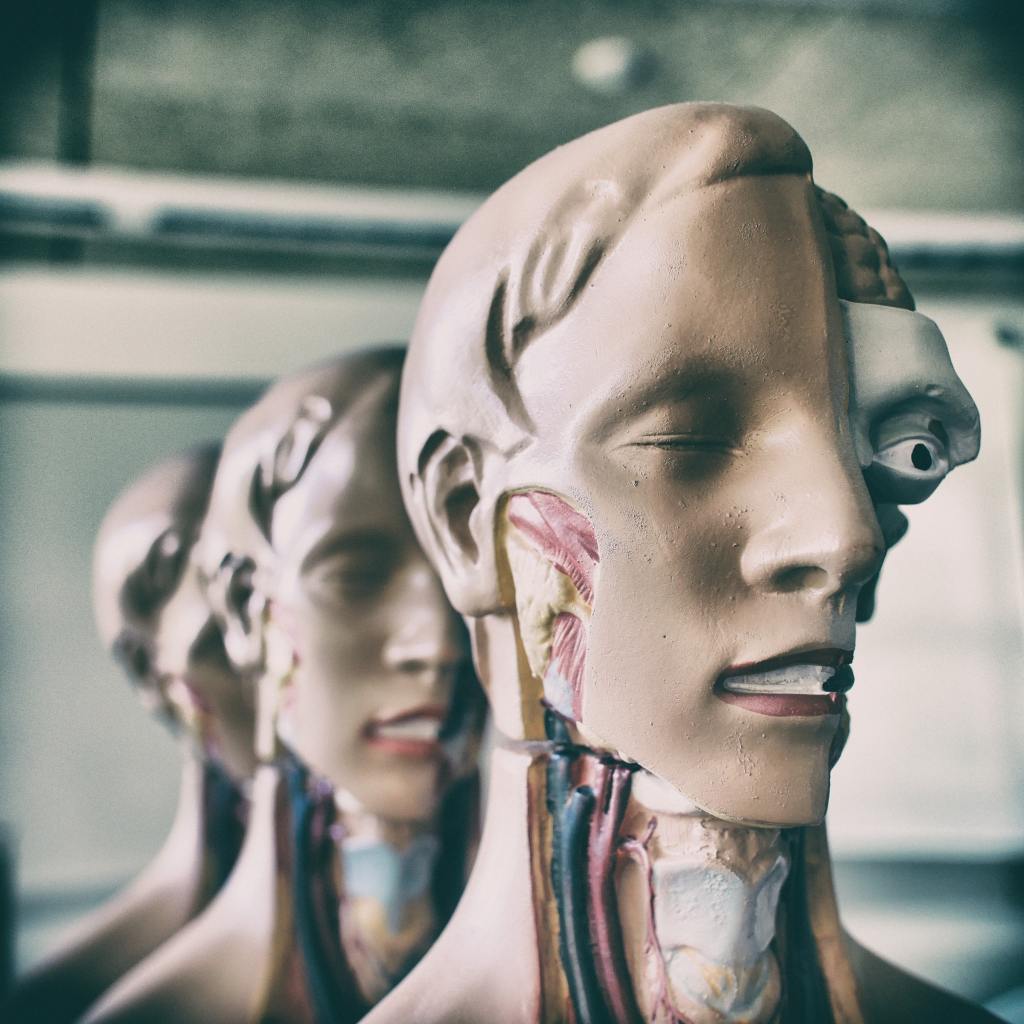

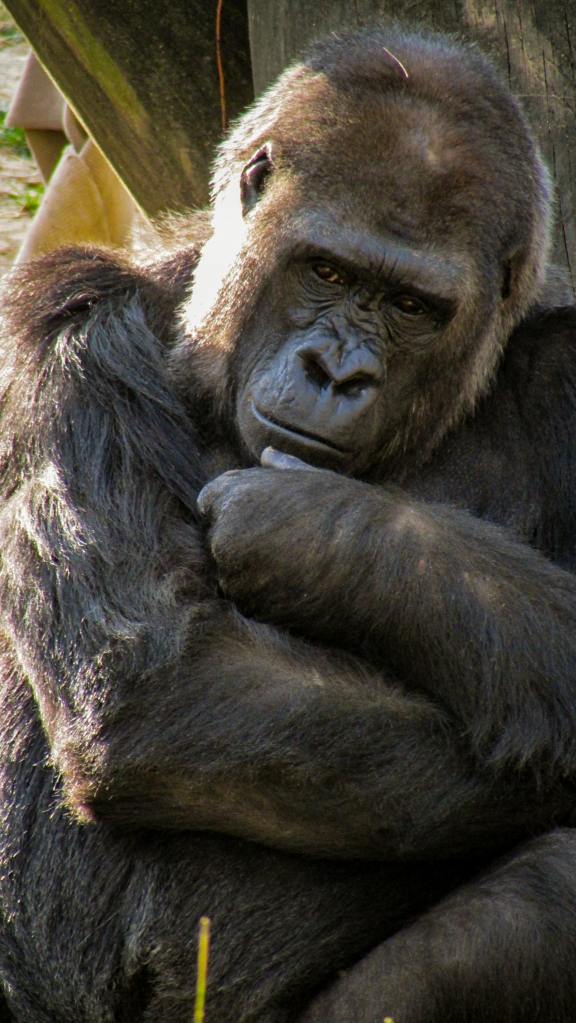

My father is a mystery to me. The National Personnel Records request brought back a few hits, all documents partially consumed by fire (for which the administer apologized) that contained just tiny bits of information. All of this makes me reflect on our limitations in knowing others. Parents, spouses, children, siblings—they all remain mysterious in some ways. And some more than others. We go through life knowing only ourselves, and not even that person fully. Consciousness brings these things to a new level, but we still really find ourselves bound by our minds. That’s why, I suspect, some of us keep trying to cram new things in there—wanting to understand others as well as ourselves. All it takes is a fire in the National Archives to wipe out entire lives. Or parts of them.

Now that her earthly time has ended, I realize my mother is also a mystery to me. It will take some time before I can sit down to write out what I knew of her life. We grow up distracted by our own needs and wants. Does a baby bird ever wonder at the enormous energy and strain on its parents as they bring food to their open beaks? Even those of us who write leave gaps—some intentional—in the records of our lives. Other people are mysteries. Wouldn’t the world be a better place if we treated them as such? Instead, we often act as if their roles (store clerk, accountant, electrician) are their lives, their essential selves. It’s all we can do, I know, to take care of our own lives. But it would be a more wonderful world if we could see others as doing just the same.