John Seward Johnson II is a sculptor whose work is instantly recognizable by a number of people. Realistic, life-size bronze castings of people doing everyday things, some are painted so as to be difficult to distinguish from quotidian humans. Others are left more abstractly colored or sized so as never to be mistaken. They are, in many ways, explorations of what it means to be human. One of Johnson’s statues, “Double Check” presents a business man sitting on a bench, checking his briefcase. It is most famous for having sat near ground zero and having confused rescuers as a real person traumatized by the events of September 11. Memorial Day seems like a good opportunity to revisit the statue that many thought was human, and which many people still adore.

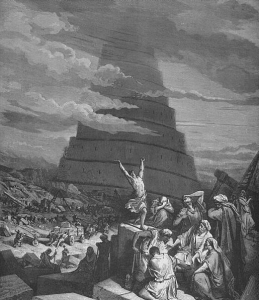

While perhaps the most obvious question a sentient being can ponder, what it means to be conscious (and in our case, human) is without an easy answer. We are animals aware of our own mortality in a way that causes many of us angst, or even terror. Humans (and perhaps other conscious animals are) notorious anthropomorphists—we think of other creatures, and even inanimate objects as being like ourselves. We can mistake statues for real people. All too often we treat others as if they were made of cast bronze. Memorial Day is for remembering, but the fallen haven’t only been the victims of the madness we call war. Violence done to others for one’s own gratification is an act of war on a personal scale. Individuals who destroy many others need to stand long before a statue and ponder.

“Double Check” has become an icon of sorts. People left gifts and remembrances for the victims of the attack on the statue. When the real thing isn’t there, sometimes a statue will do. This can teach us something about being human. As we die, at least in this culture, we are buried and a headstone becomes our statue. Our representation for the world to remember that we were here. Our progeny may lay flowers on our grave on this date some day in the future while statues that look just like humans will remain largely unchanged, asking those who remain alive to check again. To think, what does it mean to be human? And when any of us may be tempted to harm anyone else, perhaps we should gaze at a statue and consider the implications.