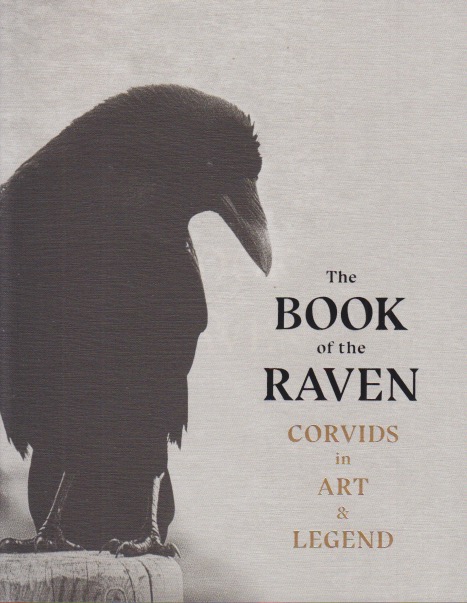

Some books are meant to be looked at. Being busy most of the time, even on weekends, I’m guilty of not enjoying art enough. The Book of the Raven: Corvids in Art and Legend is a work of art. In it Caroline Roberts and Angus Hyland have compiled paintings, photographs, and prints that feature ravens, crows, magpies, and jays, interspersed with facts, poems, excerpts, and bits of lore. It’s not a comprehensive book, nor is it intended to be. It is, however, a deeply moving book for a certain kind of person. It was an accidental find in a visit to The Book & Puppet Company in Easton. When we’re in town we like to support the independent bookstores. (I was saddened to discover that Delaware River Books, one of the two used bookstores in town, had recently closed.)

Corvids are, on a scale, about as intelligent as we are. They think, solve problems, make tools, and recognize human faces. They remember acts of kindness and reciprocate. They recognize their dead and they also play. They’re very much like us. The book includes, of course, Poe’s “The Raven,” but also other poems that draw inspiration from these smart, magnificent birds. The artwork is arresting. One of the great sins of modern life is its busyness that robs us of the time for appreciating art. And reading. Learning how to thrive in a world that has become purely about profit and ownership. Art is intended to be shared. An artist produces so that others might see. A author writes so that others might read. And corvids exist to bring wonder into our lives.

I find the strident call of jays comforting. I often hear them even on my winter walks. There are murders of crows in the neighborhood from time to time. They gather on roofs and in the trees across the street. Recently I spied a large black bird while on my daily constitutional. It had left a tree full of crows and was flying straight down the path toward me. As it flew overhead I had a good look at its tail in flight—one of the best ways to tell a raven from a crow. It was indeed a raven, and even common ravens are rare in this area. We live on the edge of their habitat. I was honored by its momentary attention. I wished I had more time, perhaps to follow that magnificent corvid and to learn from it. Instead, I will ponder The Book of the Raven with wonder.