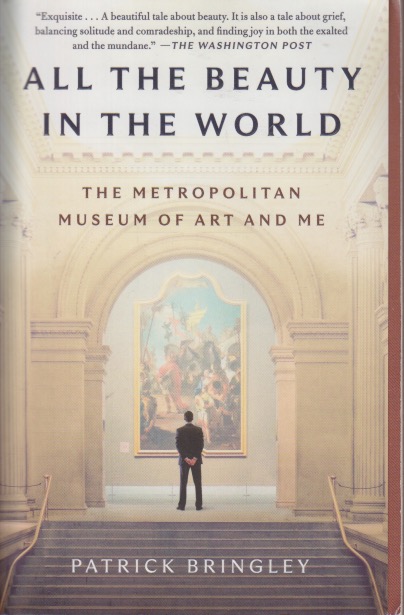

Losing someone close to you is never easy. We of our species are closely interconnected, but family is where we feel the safest and, hopefully, most accepted. There are many ways to deal with grief, but one of the more unusual is to take a job at the Met. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is world famous, of course. And Patrick Bringley, giving up a rat race job at the New Yorker (where he got to meet Stephen King, I might add), to become a guard at the Met, is the kind of thing to write a book about. He frames it as a way of dealing with the loss of his older brother prematurely to cancer. All the Beauty in the World gives you insight into a job open to just about anybody, but that has long hours and pay hardly comparable to the costs of living in New York City. Giving up the rat race to spend your days looking at, and keeping people from physically interacting with, art doesn’t sound like a bad thing.

This memoir delves a little bit into spirituality, but not in any kind of religious way. Then Bringley starts a family and after ten years decides to take his career in another direction. I’m familiar with career pivots. In my case, the choice was made for me and anybody who reads much of my writing (either fiction or non) knows that I’m trying to cope with it still. In any case, museum work—I’ve applied for many such jobs, on the curator side, over the years—isn’t easy to find unless you’re willing to be a guard. I know security guards. It’s not a job that will make you rich, but it does give you access to riches. Art is something we seldom take time to admire since, for most of us, museums are a weekend activity, and even then, only once in a while.

Museums begin with collectors. Generally rich ones. Those who can afford what the rest of us can only dream about. They’re also altruistic places, for, as well as showing off, they give the rank and file access to what we tend to value even more than money. The creative work of those we deem geniuses. Bringley doesn’t just focus on the “Old Masters”—they are in here, but not alone—demonstrating that art can, and should, include the creative work of African-American quilters and woodworkers ivory carvers from Benin. Museums are places that bring us together instead of separating us (that’s the job of politics, I guess). And this book is a thoughtful way of dealing with loss.