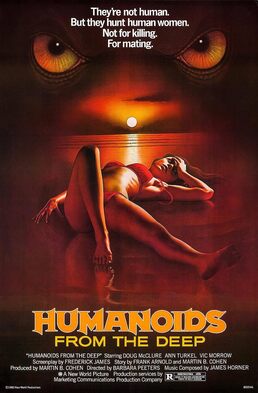

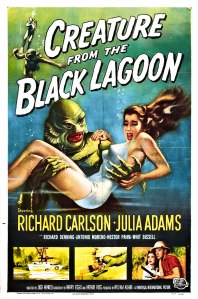

I stumbled upon Humanoids from the Deep while looking for a different film on Tubi. I had to make a quick decision (don’t ask) and I saw that Humanoids was a Roger Corman movie and figured I knew what I was getting into. In a sense I was, but B movies can surprise you sometimes. As the story unfolded my first thought was “this doesn’t look like a Corman movie.” Indeed, the direction didn’t come from Corman but from Barbara Peeters. But that wasn’t the end of the story. What is said story? Well, it’s a kind of ecological Creature from the Black Lagoon, but with a bit more of a disjointed plot. A large cannery wants to open in Noyo, California and the local fishermen all like the idea except the American Indians. Pollution has been driving off the fish and the cannery will make things worse. From the beginning humanoid creatures have been stalking the town at night.

The creatures start killing the men and raping the women. The female scientist brought in speculates that a certain hormone intended to grow larger salmon faster had leaked and coelacanths that had been eating the modified salmon became humanoid and felt the need to reproduce with human women. The creatures were inspired by the Gill Man but have ridiculous tails that give them a kind of Barney vibe. During a local festival the creatures attack the town en masse and a real melee breaks out, but the creatures are defeated with a combination of high-powered rifles, gasoline on the water set ablaze, and a kitchen knife. It’s all a bit of a mess.

Apparently Corman felt the movie wasn’t exploitative enough and hired another director to spice it up a bit, having it edited together without the director’s knowledge. To complicate things, a second, uncredited director had already been involved, so the film has three. That might help to explain why the story doesn’t really hold together. As a cheap creature feature it’s not horrible. It borrows ideas from Alien, Prophecy, and Jaws (and apparently Piranha, which I’ve never seen). It turns out to be rather nihilistic when it’s all said and done, but the creatures, apart from the tails, aren’t that bad. There are a couple of legitimately scary moments. Those of us who watch Corman movies might know to expect some deficiencies, but I was caught off guard by some of the cinematography and even some of the acting. Not bad for a movie picked with only a few minutes to decide.