So I decided to visit a Halloween store. These have been showing up with metronomic regularity in September for several years now and are usually good for a cheap thrill. My personal preference for Halloween is more somber than garish, but the affirmation that other people enjoy a safe scare has a way of drawing me in. Those who read this blog on a regular basis know that I frequently point out commonalities between fear and religion. They both seem to hover around the same orbit in the brain, and, in some accidentals are very similar. Horror films therefore often indulge in religious imagery, and monsters do not infrequently partake of the divine. So it is no surprise to see my thesis borne out in shops intending to capitalize on fear.

I will freely admit that there may be cultural references that I’m missing here. A movie that I’ve neglected, or some television show or graphic novel may be informing some of the images in ways I can’t comprehend. Nevertheless, we all know of the power of the crucifix when it comes to vampires. I wasn’t aware that the cross had horrific effects on other species of monsters as well. Take this guy here. I’m not sure what he’s supposed to be—perhaps a zombie? It seems a little too corporeal to be a demon. The teeth just don’t look right for a vampire. In any case, he seems to have an extreme reaction to religion, with the cross melting right into his skull. Is there a conversion message hidden here somewhere? Of course it could be just a chinzy attempt to scare a real religiophobe. The cross has become the backup weapon against all supernatural evil.

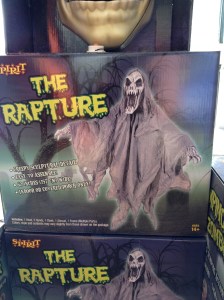

The use of a grim-reaperish ghoul rising from the grave to illustrate The Rapture was a new one on me. Last I heard only the squeaky clean and friends of the Tea Party got to go on the Rapture. (Well, the latter category might explain it.) The idea of the Rapture, as it was fabricated late in the nineteenth century, involved the chance for all the good Christians to escape before things really got rough down here for us normal folk. I would’ve thought that scary guys like this joining the heavenly crusade might take a little bit of the joy out of the occasion. Or maybe they’re being left here to haunt the rest of us. In either case it is clear that consumers respond to religious sounding language and symbolism when looking for a scare. Obviously there is plenty in the store with no religious significance at all, but finding hints of religion scattered in with the plastic scares does show a kind of Frankenstein’s monster of human sentiments and emotions. It’s only appropriate when the nights are now longer than the days.