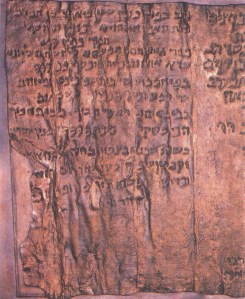

Few things travel as well as curses. Or so it seems in a news report from Serbia. Archaeologists in Kostolac, according to The Guardian, have excavated skeletons nearly two millennia old. That’s not news, since people have been dying as long as there have been people. What makes the find extraordinary are the gold and silver metal foils that have been found at the gravesite. Inscribed in Aramaic with Greek letters, these tiny missives were rolled and placed in lead tubes to be buried with the dead. Although translations of the inscriptions aren’t given, the fact that they contain the names of demons would suggest these might be curses against anyone seeking to disturb the tombs. Such devices go all the way back to the Pharaohs, and perhaps earlier. Nobody likes to have their sleep disturbed.

Serbia, for those unfamiliar with geography, isn’t exactly next door to ancient Aram. The burials and inscriptions seem to fall into the Roman Period, however, a time of cultural diversity. When cultures come into contact—in the case of Rome and prior empires, through conquest—new ideas spread rapidly. And sometimes old ideas. The Romans, in general, didn’t like competing religions. Then again, their idea of religion was somewhat different than ours. Ancient belief systems were more or less run by the state. They served to support political ends—at least they were upfront about it. Your offerings and prayers were to be given in support of the king, or emperor, and beyond that nobody really cared. Unless, of course, you were making curses.

Curses, it was believed, really worked. Even today in cultures where belief in curses persists people tend to be physically susceptible to them. We don’t want others to wish us ill. Perhaps that’s the most surprising thing about politics today. Our society has taken a decided turn towards the more secular. Candidates for political office, even if they personally believe nothing, can still cast curses on those who are different. They can claim support of their “faith” to do so as well. Words, in ancient times, were performative. They meant something. Curses were taken seriously because if someone were serious enough to say it, they probably meant it. They could be written down and preserved beyond death. Today, however, words are a cheap commodity. You can use them to attain your personal ends and discard them once they’ve outlasted their usefulness. Perhaps we do have something to learn from the past after all.