The end of the world, as we know it, is really more recent than we think. Yes, Christians of a certain stripe have been looking for the second coming since the first leaving, but that detailed map of how we’re living in the end times, courtesy Hal Lindsey, is a new thing. Here are the fast facts.

First and second centuries, Common Era: early Christians tended to think Jesus would “be right back.” When that didn’t happen they began to look in the Bible for reasons why and started to develop theologies to cover the bases.

Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages: settled in for the long haul, theologians developed eschatology. Although that sounds like a disease, it’s actually a system for thinking about how the end of the world will come down. There were conflicting theories. The two main flavors were premillennialism and amillennialism.

Early Modernism: Protestants came along and searched the Bible for minute clues to make into a system. In response, postmillennialism became a thing. Now there were three options. Various phases were discussed: tribulation, resurrection of the dead, and the already-met millennium.

1820s: William Miller, a Baptist minister, began number-crunching and figured the end of the world would take place by 1843. His followers, “the Millerites,” continued on after what was called “the Great Disappointment.”

1830s: John Nelson Darby, a Plymouth Brethren leader, came up with Dispensationalism, a scheme that divides history into eras, or “dispensations.” He thought we were living near the end of that scheme about 200 years ago. The idea of “the rapture” was added to the other phases.

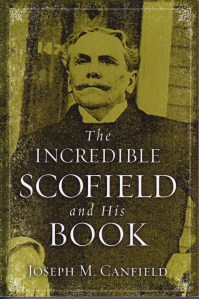

1917: Cyrus I. Scofield, published the Scofield Reference Bible. A man with little formal education (and a “colorful” background), he applied Darby’s dispensations in his Bible, giving the United States a road map to the end times.

1970: Hal Lindsey, a seminary educated evangelical, published The Late, Great Planet Earth. It became the best selling book (classified as nonfiction) for the entire decade. New ideas, such as “the Rapture” and “the Antichrist” began to be read back into the Bible. The book was made into a movie.

1976: David Seltzer, a Jewish screenwriter, penned The Omen. The movie made use of Lindsey’s adaptation of Scofield’s adaptation of Darby’s ideas. The wider public, seeing it on the big screen, believed it was about to happen.

2000: the world still didn’t end, either with a second coming or Y2K, as many predicted. Round numbers will do that to people. It didn’t stop predictions of the end of the world.

2012: the Mayan calendar gave out. A movie was made. People believed. Apocalypse averted.

2024: you fill in the blanks.