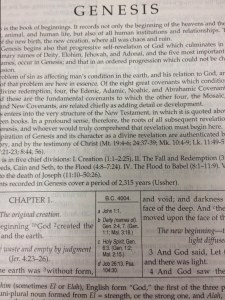

The average reader has difficulty sorting out what’s biblical or not. For example, when Cyrus Scofield began putting 4004 BC [sic] as the date of creation in his annotated Bibles, people thought the date was biblical. It was, literally, “in the Bible.” I used to tell my students that there’s a cultural belief that everything bound between the covers of a Bible is biblical. If so, I’ve just become biblical myself. I must say, it comes with mixed feelings. For the many people with whom I’ve worked on the New Oxford Annotated Bible, having their names inside is an expectation. Employees, however, sometimes make it in, too, in a prefatory way. I was touched to see my moniker there, on Bible paper, amid Holy Writ. Almost life-changing. A little scary.

Imagine a post-apocalyptic world. (I know, it’s easier now than it was just a few short months ago.) What if all books were wiped out except a copy of the book fondly abbreviated NOAB? Some Leibowitzian monk might come across it, and, recognizing that it’s sacred dare to open it, not comprehending the language but eager to begin again. Am I ready to be in such a book? Nobody reads prefaces, I know, but this is the widest circulation my humble family name has ever achieved. In there with Joseph, Job, and Jesus. It’s heady stuff. I’ll be on the shelves of used bookstores from now on. For a guy who’s books have been printed only in the 300 run range, this is dizzying. And not too bad for being only an administrator. None of my deans ever made it into the Good Book.

Surely there’s some grim responsibility that accompanies becoming biblical? Some consummation devoutly to be wished? Looking around at my fellow biblical characters, I’m not so sure. Many cases of men behaving badly surround me. None of them, I expect, had intended to be biblical either. Time and circumstance led to their elevated status. Modern biblical people tend to be famous only among their own guild. Some gain wider recognition, to be sure, but none share the name recognition of those recalled by the unknown recorders of sacred scripture. I’ve written books of my own, and been acknowledged as a scholar and editor in other peoples’ books, but never before have I found myself in such exalted, if accidental company. Where does one go from here? A Herostratus of Holy Writ? I can’t help but wondering if Jeremiah started off working in a cubicle.