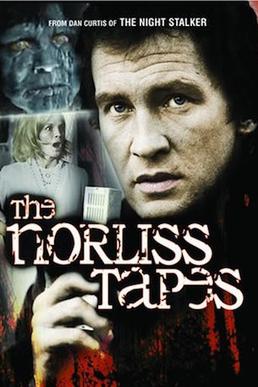

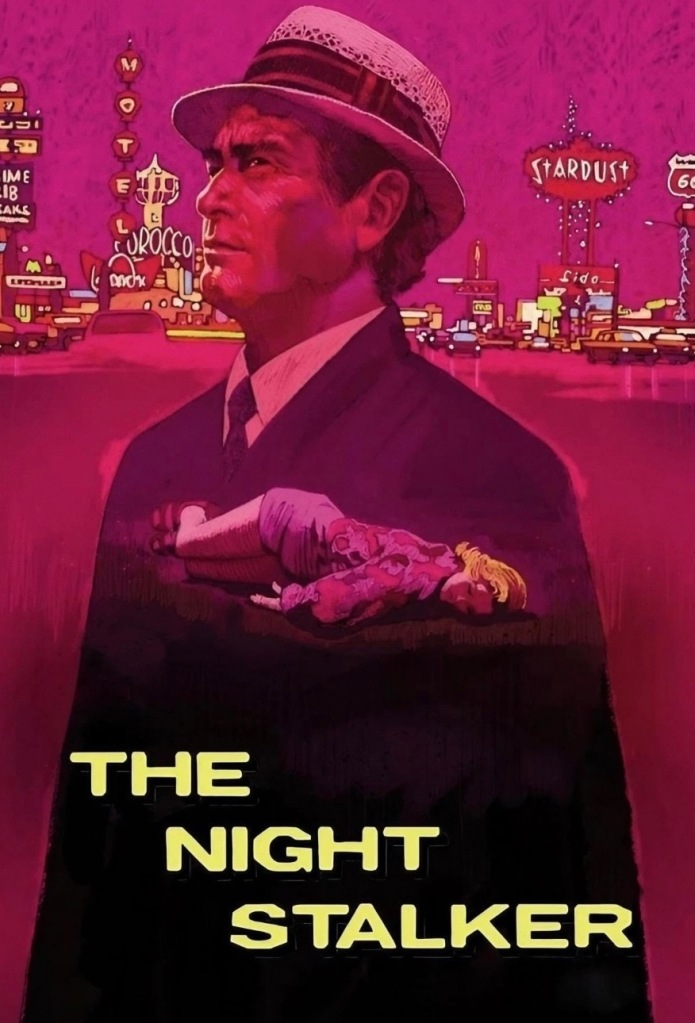

Dan Curtis was the mind behind Dark Shadows, an important part of my childhood. Reading about his work in film and television, I learned that he produced a lot more than Barnabas Collins, and was an influence in horror in his own right. A friend recommended that I find The Norliss Tapes, which I did. This made for television movie was cut from the same cloth as The Night Stalker, which Curtis also produced. The ending of the movie makes clear that The Norliss Tapes was a pilot for an intended series that never materialized and is a good representation of religion and horror, which is likely why it was recommended to me. Here’s the story. David Norliss was given a large advance by a publisher to write a book debunking the supernatural. Before he can, he goes missing, leaving behind a set of tapes explaining what happened. The first tape is the pilot episode.

Norliss is contacted by Ellen Sterns Cort, a widow who claims to have had a supernatural episode. Upon following her dog to her late husband’s studio one night, she encounters her undead husband. She shoots him, but the police can find no evidence of any body. It’s revealed that he purchased an occult scarab ring that permits him to return to life to raise a demon who will, in turn, bring him back to real life. To get the raw materials he needs (such as blood) he has to kill a few people and this again alerts the authorities but they insist on covering it all up. Removing the ring from his finger will stop him, but that’s easier said than done. At the end the demon is stopped but this is just the end of the first tape. His publisher starts to play the second tape.

Dan Curtis productions have a certain feel to them. I’m not sure how directors and producers do that—I’m not sure of all the tools they have in their box. What is obvious is that watching The Norliss Tapes brings back echoes of Dark Shadows. That’s not surprising since Dark Shadows wound down just two years before the Norliss Tapes came out. The Night Stalker was sandwiched between them, but Kolchak: The Night Stalker was not a Curtis production and doesn’t have a Curtis feel to it. Even though I’d never seen Norliss before, it was nostalgic watching the movie for the first time. There’s a trick to it, I just don’t know what it is.