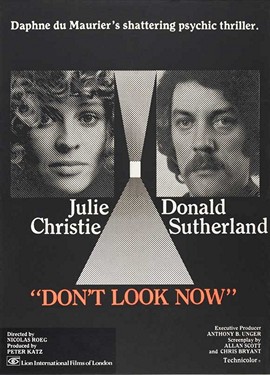

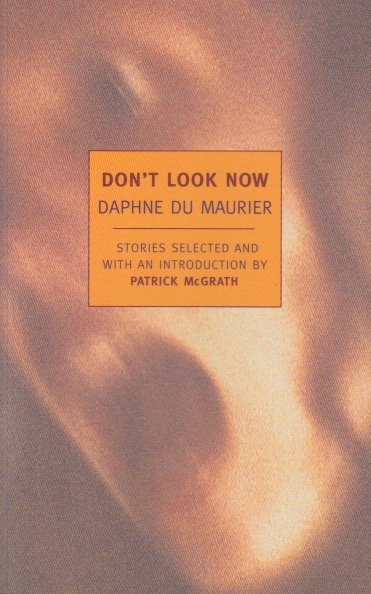

When you think of Daphne du Maurier’s film adaptations, Alfred Hitchcock probably pops to mind. He shot Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, and The Birds, based on her works. One non-Hitchcockian adaptation is Don’t Look Now, by Nicolas Roeg. I’d made the decision to read the story first—which was a good idea—but it was long enough back that I couldn’t recall many details. This was also good. Don’t Look Now was the main release by British Lion, in Britain, with the B movie, The Wicker Man, as its follow-up. While writing a book about the latter movie I’d wondered why this one was chosen as for lead billing. It’s certainly more mainstream, and an art film in many ways. Typically labelled a “thriller,” it’s also called “horror,” causing me to question the relationship between the two. In any case, the movie.

Since this was released in 1973 I won’t worry about spoilers. The film is a fairly faithful adaptation of du Maurier’s story as well. Laura and John Baxter are in Venice, trying to recover from the accidental drowning of their daughter. John has work there, restoring a church—there’s plenty of religious imagery—and Laura befriends two older women. They’re sisters and one of them is blind but also psychic. Heather, the psychic, claims to see their drowned daughter and Laura finds relief and comfort from hearing about it. John is skeptical, but, Heather claims, he also has psychic abilities. John begins to think he’s seeing their daughter still alive and she leads him down isolated alleys—this is dangerous because there’s a serial killer on the loose. John then thinks he sees Laura with the women after she has flown back to England to attend to their son at his boarding school.

Movies, like stories, are open to interpretation. Mine is that the psychic phenomena in the film are portrayed as real. I had the same impression from du Maurier’s story. Much like The Wicker Man, appreciation for Don’t Look Now has grown over the years. It was fairly well received upon release, but is now considered even better than it was at the time. Maybe not as essential as some Stephen King movies, it is nevertheless believed to be one of the more important films on the horror palette. I’d been prompted to watch it by several references I’d recently come across. Typical for me, however, I took it in the wrong order, having seen The Wicker Man years ago. Classics back then, it seems, took longer to be recognized.