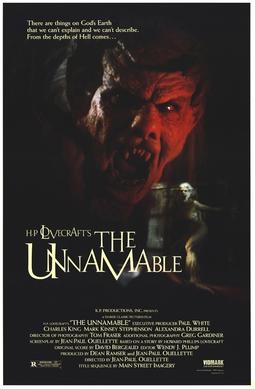

There is no shortage of Lovecraftian horror movies out there. I watched The Unnamable because I found it on a list of dark academia movies. And also, well, it’s horror. I’ve most likely read Lovecraft’s original story at some point in time, but I didn’t remember it at all. The dark academia part comes in because it involves college students and a haunted house. A low-budget offering, this is hardly great cinema. It’s not sloppy enough to qualify as a bad movie. That puts it somewhere around “meh.” The film opens with Joshua Winthrop being killed by the monstrous daughter that he keeps locked in a closet of his house. Then, in the present day (the movie is from 1988) three college guys talk about it and the skeptic decides to spend the night in the house to disprove the monster tale. He is, of course, killed. Although his two companions don’t go looking for him, others end up in the house.

A couple of upperclassmen looking to score with freshmen coeds, talk two women into going to the house with them. As they start to enact their plan, the monster kills them one-by-one, leaving the virginal final girl alive. Meanwhile, the other two students whose friend was killed, also come to the house. They manage to rescue the final girl and escape the creature by invoking the Necronomicon’s spells. The music cues are often comical, suggesting that this isn’t to be taken seriously. They also spoil the dark academia atmosphere. For me, a horror film works best if it’s either clearly horror or clearly comedy horror.

It did, however, raise a question in my mind. Dark academia and horror do have some crossover. H. P. Lovecraft often had professorial types as his protagonists. Was he writing a form of dark academia? It’s difficult to say. Lovecraft’s work was known as “weird fiction” in his time, and it has become its own kind of genre. (Just try to publish in the rebooted Weird Fiction without your Lovecraft cap on and see how you fare.) I’ve been pondering genres for quite some time, and since I watch movies because they’re free or cheap, often, I see some unconventional fare. There’s no question that The Unnamable is horror. When the movie ended I was sad for the monster. She’d been living according to her nature, and really didn’t deserve the treatment she received from a bunch of trespassers. Not a great movie, it nevertheless made me think.