Free will. I’ll go on the record as a proponent. Any kind of determinism gives me the willies. At times, however, it does feel as if we’re merely pawns. Katy Hays deals with the concept of fate, and the occult world of tarot, in The Cloisters. The writing is quite compelling and the story moves along at a good pace. It follows Ann, a graduate from eastern Washington who wants to get away from the town where her father was killed. She accepts the offer of a summer program at the Met in New York City, but because of a mix-up ends up at the Cloisters instead. I’ve never actually been to the Cloisters, but this novel makes me want to go. At this museum of Medieval and Renaissance art, Ann works with Rachel, another assistant, Leo, a gardener, and the curator, Patrick.

Rachel has been at the Cloisters for some time and Patrick, her boss, has become enamored of tarot decks and their history. He’s been seeking perhaps the oldest complete deck known and has come to believe that perhaps the cards do have the ability to tell the future. Ann befriends Rachel. The two begin to make discoveries, particularly Ann, but Rachel, who is independently wealthy, manipulates her, taking advantage of the fact that Ann never wants to return home. Then Patrick is poisoned. I won’t reveal whodunnit here, but the last half of the book has several twists that make you reassess whatever conclusions you may have drawn. It’s a fascinating story, well told.

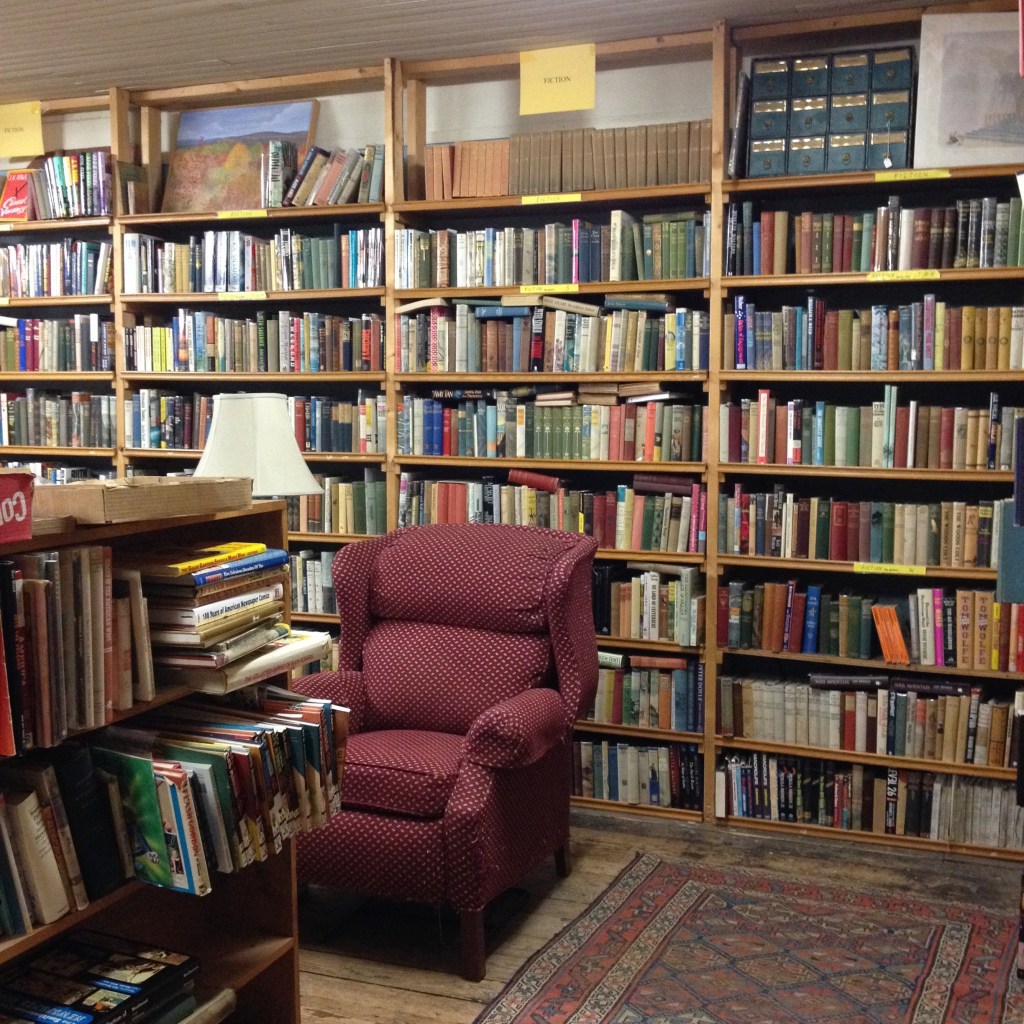

This novel is another example of dark academia. Much of it takes place in the library of the Cloisters and Patrick holds a Ph.D. while Rachel is a graduate student. Ann is about to enter a doctoral program. All of them have some fairly dark secrets in their lives. And all of them are driven. The story has elements of social commentary as well, particularly concerning how life in New York City will drive people to extremes when the competition makes this necessary to survive. Although three of the four commit crimes, they are all likable people. Three of them are academics as well. All four are quite intelligent. I was drawn into this tale from the start and even as the darkness was revealed couldn’t bring myself to dislike any of the characters. Some novels have antiheroes that you just can’t feel for. The Cloisters moves in the other direction, and it does make you wonder just how much choice you actually have and how much is left to fate.