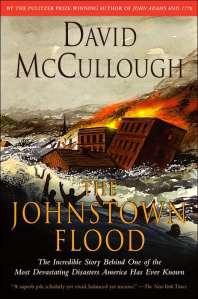

Floods always have a whiff of old Noah about them. I first heard of the Johnstown flood from a minister who has had a profound impact on my life. He had been in Johnstown for the 1977 flood, and that led me to learn a little bit about America’s first great natural disaster. I decided to follow up David R. Montgomery’s flood book by David McCullough’s The Johnstown Flood. Like most stories of human tragedy, this devastating flood combined elements of human culpability with nature’s own inscrutable workings. The 1889 flood came during an unusually heavy rainstorm. Some years before, an exclusive millionaire’s club had repaired an artificial dam rebuilt for the recreation of the wealthy high above the town. Records show the repairs to have been lackluster—at one point they purchased hay to act as cheap fill. Although the members knew of the danger they did nothing to avert the deadly potential a breech in the dam would inevitably cause. When the dam burst during the storm, over 2200 people died.

Floods always have a whiff of old Noah about them. I first heard of the Johnstown flood from a minister who has had a profound impact on my life. He had been in Johnstown for the 1977 flood, and that led me to learn a little bit about America’s first great natural disaster. I decided to follow up David R. Montgomery’s flood book by David McCullough’s The Johnstown Flood. Like most stories of human tragedy, this devastating flood combined elements of human culpability with nature’s own inscrutable workings. The 1889 flood came during an unusually heavy rainstorm. Some years before, an exclusive millionaire’s club had repaired an artificial dam rebuilt for the recreation of the wealthy high above the town. Records show the repairs to have been lackluster—at one point they purchased hay to act as cheap fill. Although the members knew of the danger they did nothing to avert the deadly potential a breech in the dam would inevitably cause. When the dam burst during the storm, over 2200 people died.

Wrenching, like most natural disaster accounts are, the story of human misery raises questions of theodicy and basic humanity. Members of the club were those who ran Pittsburgh in the days before their steel mills fell silent. Apart from a few like Andrew Carnegie, who gave generously to those in dire need after the tragedy, most of club members gave nothing to the relief effort for what their negligence helped cause. They hadn’t even hired an engineer to consult about their dam project when they decided to rebuild it. Lawsuits filed failed to touch them; the suffering of thousands failed to move them. Fast forward just over a century—as the towers of the wealthy came down the working class tried to save as many as they could, some at the cost of their own lives. We all know who are regarded as the heroes.

“Was it not the likes of them [club members] that were bringing in the [foreign workers], buying legislatures, cutting wages, and getting a great deal richer than was right or good for any mortal man in a free, democratic country?” McCullough’s words, explaining the sense of those who’d lost everything to the idle dalliances of the leisured class, still ring true in the world of one percenters. Often it takes a tragedy to bring society’s inequalities into focus. As a nation we’ve gone on to have even more costly disasters since May 31, 1889, but the instability built by corporate greed has kept pace, indeed, perhaps even surpassed what it was back then. “And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually,” or so I have it on good authority.