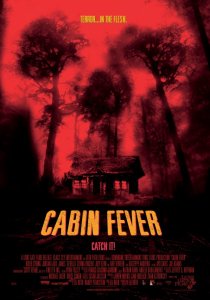

It’s a sure sign that work is growing overwhelming when I’m too tired to watch my weekend horror movies. Well, I decided to fight back the yawns and pull out Cabin Fever this past Saturday night. I’d seen the movie before, and I’m not really a fan of excessive gore. The acting isn’t great and the characters aren’t sympathetic, yet something about the story keeps me coming back. In short, a group of five teenagers (it always seems to be five) are renting a cabin for a week when they get exposed to a flesh-eating virus. They end up infecting just about everyone in the unnamed southern town before they all end up dead. It doesn’t leave much room for a sequel, but that hasn’t stopped one from being made. One of the unfortunate victims of the virus is torn apart by a mad dog. The locals, fearing their safety, decide to hunt down the surviving youths.

On the way to the now gore-smattered cabin, one of the locals mutters that they’ve been sacrificing someone—a natural enough conclusion when body-parts are scattered around, I suppose. He says, “it ain’t Christian.” Well, yes and no. Sacrifice is at the putative heart of Christianity, although human sacrifice (beyond infidels and women) was never part of the picture. As is often the case with horror film tropes, the victim who has been dismembered is a woman. The guys whose deaths are shown are all shot. Now, I have no wish to attribute profundity where it clearly is not intended, but there does seem to be a metaphor here. Our society and its staid religion tolerate the victimization of some over others.

One of the hidden treasures of the best of horror movies is the social commentary. George Romero made an art form of it in Night of the Living Dead and its follow up Dawn of the Dead. Many other writer/directors have managed to do it quite effectively. We can critique our world when hidden behind the mask of the improbable. While the commentary for Cabin Fever may be entirely accidental, I still find a little redemptive value in it. That, I suppose, is the ultimate benefit of social commentary—it is true whether intentional or not. Is there a larger message here? I wonder if the fact that when women are victimized no one survives is pushing the metaphor a little too far. It’s hard to say; I’ve been working a little too much lately.