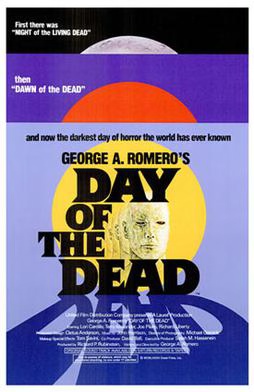

When we lived in New Jersey our internet wasn’t fast enough for streaming. I’d watched George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead, but I was never able to find a DVD of Day of the Dead. Well, it finally came around to streaming (thanks, Freevee), so I was able to complete the trilogy. It doesn’t get discussed as much as the previous two, and it’s clear that it doesn’t come up to their level. Still, the discussions of larger issues—God, civilization, and military power—are worth pondering. There are a few jump startles but less intensive gore than the previous two, until well into it. So, here’s the story: a base of operations has been set up in Florida where the military is overseeing civilian scientific experiments on the animated dead. The military guy in charge is a real jerk and threatens to shoot those who don’t comply. Also, there’s just one woman among them (who made that decision?).

As might be expected, things go haywire. The head scientist, “Frankenstein” to this crew, is trying to teach the dead not to eat the living—to coexist. The living are hopelessly outnumbered, and despite the Jamaican civilian, John, suggesting they go to a deserted island and start all over, everyone seems content to hang out and fight each other. In the end, military overreach leads to everyone being killed except John, Sarah (the woman scientist), and Bill, who seems to be Irish. In the end the three of them fly to a deserted island and you kind of get the idea that this will be a bit more of an R-rated Gilligan situation. The film is campy and there is a comic tone throughout despite the serious issues raised and the actual horror elements (blood and zombies lurching out of the dark).

It actually also attempts to explain how the dead continue to move and why they eat with no internal organs. The brain, down to its reptilian base, retains the eating instinct. Frankenstein, before being killed by the military, is training the promising dead, especially Bub. In the end, Bub kills the military guy. As far as the story goes, it seems to send mixed messages. The good guys do prevail and the dead, at least Bub, is more righteous than the fascist military that holds sway via constant threat. One does get the sense that Romero was having fun with his zombie movies and some of the special effects were quite good. I’m glad to have finished the trilogy, but I don’t think I’ll bother watching the remake, which was, back in the day, fairly easy to find on DVD. They’re never as good as the dead they try to reanimate.