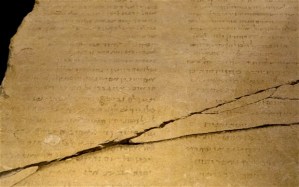

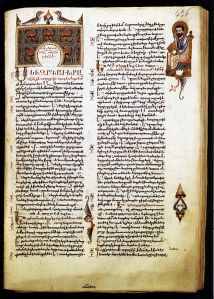

A few weeks back, probably several now actually, the New York Times ran a story about the Bible. In this age of declining interest in the Good Book such things catch my attention. Of course, the reason that the story ran was because of the money involved. Let me explain. Or at least give the headline: “Oldest Nearly Complete Hebrew Bible Sells for $38.1 Million.” Money talks, even when it comes to Scripture. The story was about the auction of the Codex Sassoon, which went to a museum. Most regular Bible readers aren’t aware of the textual criticism behind their favorite translations—yes, even the good ol’ King James. You see, no original biblical manuscripts survive. Not by a long shot. Every biblical manuscript in the world is a copy of a copy of a copy, etc. And these copies differ from one another. Often quite a bit.

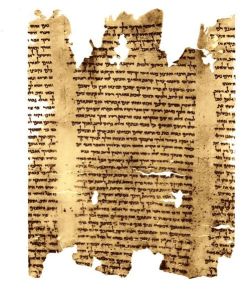

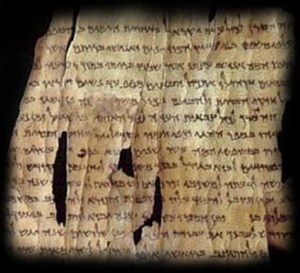

Textual criticism is the job of comparing manuscripts and using scientific—yes, scientific—principles to determine which one better reflects what was likely original. Since we don’t actually have the original we can’t say. Those who hold views of extreme reverence for one translation or another have to resort to divine guidance of the textual critics to make the case. For example, they might argue that God inspired the translators of the King James to follow one manuscript rather than another. The King James was based on manuscripts known at the time (only about six of them) and far older manuscripts—inherently more likely to reflect earlier views and potentially closer to the original—have been discovered since then. And are still discovered. That was one of the reasons behind all the fuss over the Dead Sea Scrolls. They represent some of the earliest biblical manuscripts ever found.

The Bible is an identity-generating book. In this secular age, the failure of “the educated” to realize this simple fact often leads to underestimation of the importance of religion. It motivates the largest majority of people in the world. We should pay attention to it. It doesn’t make headlines too often, though. Instead, politicians who pretend they respect the Bible but live lives about as far from its precepts as possible, gather the limelight. When money gets involved the Bible becomes interesting again. We think about that thirty-eight-million. What we might do with that kind of money. How we might be able to pay somebody to paint that fence that desperately needs it, or better, to help those in desperate need. The many victims of capitalism. Where their heart is, there their treasure will be also.