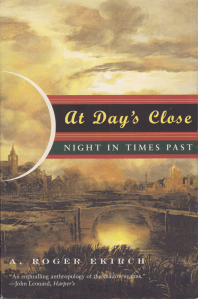

Some historians, I suspect, despair of the volumes already written on all periods, ancient and modern. History, however, can cover a variety of segments of time. A. Roger Ekirch, for example, thought to write a fascinating history of darkness. At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past is a thoughtful exploration of what night has historically meant. For those of us born in the era of constant light, the realities of what it was like after dark in the past are almost unimaginable. I’m sure Ekirch didn’t intend it to be so somber, but the reality of frequent crime in unlit regions made reading much of this book a sober experience. Confident of their ability to get away with it, many up until modern times took advantage of the night to commit all kinds of crimes. Makes you kind of want to check the door locks once again before turning in.

Some historians, I suspect, despair of the volumes already written on all periods, ancient and modern. History, however, can cover a variety of segments of time. A. Roger Ekirch, for example, thought to write a fascinating history of darkness. At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past is a thoughtful exploration of what night has historically meant. For those of us born in the era of constant light, the realities of what it was like after dark in the past are almost unimaginable. I’m sure Ekirch didn’t intend it to be so somber, but the reality of frequent crime in unlit regions made reading much of this book a sober experience. Confident of their ability to get away with it, many up until modern times took advantage of the night to commit all kinds of crimes. Makes you kind of want to check the door locks once again before turning in.

Much, but increasingly less, of our lives is spent in sleep. The advent of artificial light has led to changes in lifestyle that, according to biology, aren’t terribly healthy. The natural rhythms of sleep and wakefulness may be challenged by jobs or enticements to stay up late and surf the web or any number of other factors. Now that light has become so very portable in the form of smart phones and tablets, even less of darkness remains. Although it’s a bit repetitive and not laid out chronologically, At Day’s Close contains many provocative observations about the dark. There’s even a bit about monsters.

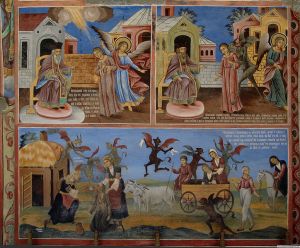

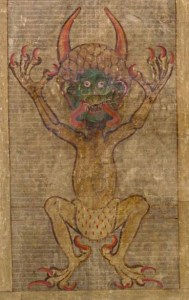

Night has always been symbolic. Death and fear were associated with night early on, and we still call the era of scientific progress the Enlightenment. Churchmen (for it was an age of such) tended to condemn night as evil, the Devil’s time. Not all agreed, for some considered the dark a creature of God and complained of the hubris of setting up lights at night. The religious symbolism of night is very rich and very ancient. Those of us used to artificial light have difficulty imagining what it took to navigate after dark in ages past. More than an annoyance, night could be a truly dangerous time. Dreams, once mainly the products of the night, also had religious significance before being rationally explained. The industry of banishing night also has, in some respects, the effect of banishing dreams. We should stop and think before we put night to flight. Half of our time is spent in darkness, and all of our time is highly symbolic.