According to goodreads.com, I read 83 books in 2013. The beginning of a new year seems a good time to assess what is memorable among the reading material of the previous twelve months. I am an eclectic reader: this informed my research when I was teaching in higher education—nobody can know everything, and it doesn’t hurt to keep an eye on what fellow researchers in “unrelated” areas are doing. I always throw in a healthy dose of novels as well. Among the novels, some of the most profound were those written for younger readers (each of the books discussed here, by the way, can be found discussed in more detail by selecting the category “books” at the right on this blog). Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, Ransom Rigg’s Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, and Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief all stand out as particularly profound. They are all, as young adult books tend to be, stories about coming to terms with the adult world. The theme of death weighs heavily in all of them. In none do the children take refuge in religion.

Among the non-fiction offerings, revisiting my most memorable also reveals trends, I think, in how religion might be usefully applied to an increasingly secular culture. It is no easy task to choose favorites, but I see that I read three books about comic books: Mike Madrid’s The Supergirls and Divas, Dames, and Daredevils, and Christopher Knowles’ Our Gods Wear Spandex. The work of Jeffrey Kripal started me on the quest of taking superheroes seriously as sublimated religious figures. Clearly that is the case, as has become increasingly apparent in top-grossing movies. Another set of books (Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, John Angell and Tony Marzluff’s Gifts of the Crow, and Curtis White’s The Science Delusion) highlighted some of the deeply rooted flaws of a materialist reading of the world, whether they intended to or not. Robin Coleman’s Horror Noire, and Susan Hitchcock’s Frankenstein indicated that monsters are among the most eloquent of social critics, even when they have little to say. I would recommend any of these books without hesitation.

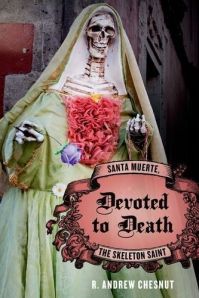

Some of my reading was on specific religious traditions. Maren Cardin’s Oneida, Hugh Urban’s The Church of Scientology, Sean McCloud’s Making the American Religious Fringe, and Andrew Chestnut’s Devoted to Death each showcased either a single or several traditions that have emerged in the last century or two that have had a striking impact on America’s religious morphology. Katie Edward’s Admen and Eve is a great example of how businesses have figured out that a religiously hungry society will buy, if marketing pays attention to religion. Among the most powerful books I read were Susan Cain’s Quiet and Jonathan Gottschall’s The Storytelling Animal. Being human is, after all, the most religious of experiences. Starting with fiction, I’ll end with fiction. The novels for adults I remember most vividly are those with strong female protagonists: Sheri Holman’s Witches on the Road Tonight, Piper Bayard’s Firelands, and Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian.

This blog offers me a chance to give brief sketches of books that have much more to say than a few words might summarize. The fact that religious ideas and themes might be found in such a range of books underlines once again that we live in a religious milieu, whether we want to admit it or not. Read on!