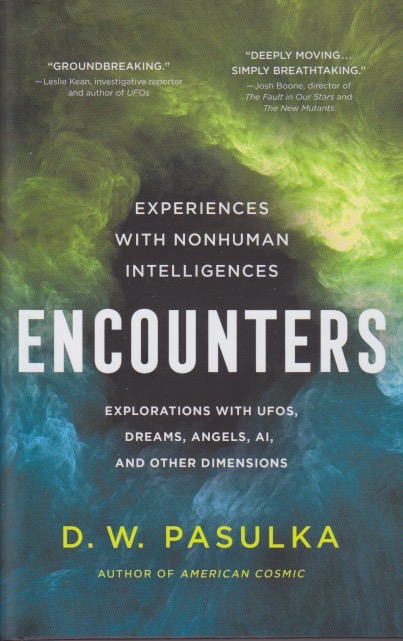

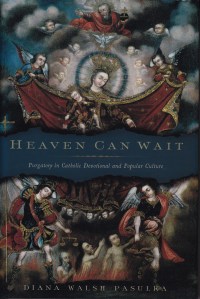

Why do we read, if not to expand our minds? I’ve read all of Diana Walsh Pasulka’s previous books but Encounters is mind-blowing. I feel particularly honored that a scholar of religion has been able to put together so many pieces of a very strange puzzle. Pasulka’s first book was about Purgatory. Having grown up Catholic that seems a natural enough choice. Her second book, American Cosmic, focused on a topic that academics were just starting to address at the time—UFOs. That book justly earned her acclaim. Encounters takes a few steps further into the mysteries of being human. Those who experience UFOs have much in common with people who have other extraordinary encounters. The profiles in this book will give you pause time and again.

Many of us have felt that the unfortunately successful government strategy of ridicule toward experiencers has been a blanket covering up the truth for too long. I was interested in UFOs as a child and was unmercifully teased for it. One of the reasons I was interested was that I learned, when I was about eleven, that my grandfather had been interested as well. I was only two when he died, so there was no way to learn this personally. It came through discovering a couple of his books that my mother had kept. Since she was one of five siblings, it’s difficult to say if he’d had any other books on the subject, but being a reasonable kid, I wondered why this was a forbidden topic. You could talk about ghosts (at least a little bit) and be considered “normal.” Mention UFO’s and you’re insane.

When the Navy’s video recordings of UFOs—renamed UAPs—were released in 2019, there was silence in the room for about half an hour. Serious people began to realize there might be something to this. Of course, those who’d internalized the ridicule response continued to fall back on it, perhaps as a defense mechanism. That revelation has allowed, however, serious consideration of what is a very weird phenomenon. I’ve deliberately avoided saying too much about what Pasulka covers in her book. As I generally intend when I do this, what I’m hinting is that you should read this book. You should do so with an open mind. If you do, you might find yourself thinking in some new ways. Of course, some will ridicule. Others, however, may walk away with an expanded perception of reality.