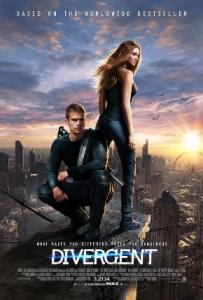

Self-denial, no matter what its motivation, is a religious ideal. In its more extreme forms it becomes martyrdom, but most religions agree on the value of taking less for yourself so that others might have more. This has been running through my head since seeing the movie Divergent. I read and posted on the book some time ago, but having recently seen the movie—a fairly faithful adaptation to the novel—I was forcefully reminded that this is a dystopian parable. In the future, society is divided into different factions, based on a person’s predisposition. This is done to keep the peace, and the factions seem to get along until suspicion grows about the group called Abnegation. The Abnegation faction is moved by pity and compassion for others. They are the consummate self-deniers, not thinking of themselves to the point of limiting time they can spend looking in a mirror. Others are the focus. Naturally, those who see the utter selflessness of others wonder what they’re really up to. Suspicion grows that this group is after wealth, in the form of food, secretly stockpiling it for themselves. Nobody would give up for themselves so that others can have more.

Self-denial, no matter what its motivation, is a religious ideal. In its more extreme forms it becomes martyrdom, but most religions agree on the value of taking less for yourself so that others might have more. This has been running through my head since seeing the movie Divergent. I read and posted on the book some time ago, but having recently seen the movie—a fairly faithful adaptation to the novel—I was forcefully reminded that this is a dystopian parable. In the future, society is divided into different factions, based on a person’s predisposition. This is done to keep the peace, and the factions seem to get along until suspicion grows about the group called Abnegation. The Abnegation faction is moved by pity and compassion for others. They are the consummate self-deniers, not thinking of themselves to the point of limiting time they can spend looking in a mirror. Others are the focus. Naturally, those who see the utter selflessness of others wonder what they’re really up to. Suspicion grows that this group is after wealth, in the form of food, secretly stockpiling it for themselves. Nobody would give up for themselves so that others can have more.

As I watched the movie I thought about religious groups that preach self-denial. Granted, I’m only one person, but growing up that was the message I continually heard loud and clear in the teachings of Jesus, according to the Gospels. Deny yourself so that others might have more. The deeper I became involved with the church, however, the rarer I found such behavior. By the time I reached college, I still hadn’t figured out that religion had become an industry, like any other. A service industry, to be sure, but it still had CEOs and treasurers and, increasingly, political power. The political seduction of religion already had a history by the time I became aware of it, but I still believed that self-denial was at the core of true religion. Perhaps the factions I heard whispering around me were right. Perhaps there was something more driving all this.

In Divergent, the belief in selflessness leads to self-sacrifice. In many feel-good movies, this leads to an expected resurrection. Here the future is bleak, and the dead remain dead. There is a kind of resurrection as the Dauntless faction comes out of its stupor, but the movie leaves the viewer wondering if there is a future after all. Is there a place in the world for those who legitimately want everyone to share? I think that every time I find myself driving. Behind the wheel, selfish maneuvers that lead to little, if any, ultimate gain seem to be deeply embedded in those who want to get there first. Abnegation, it seems, is a danger on the road. Driving, it seems to me, is a real test of someone’s religious convictions. Perhaps it is that one has to realize that the vehicle in front of you contains another human soul. Or perhaps it is that the fragmentation of society has already gone too far and those who don’t take for themselves are not emulated, but consumed.