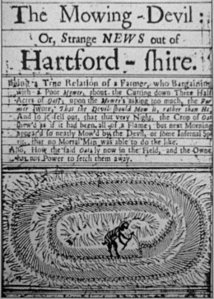

Validation. We’re surrounded by it. Now that we have the internet, everyone seems to want us to verify who we are. And we were told as kids that there are no such things as trolls! Personally, I have no idea why a hacker would want to be me. I mean for destabilizing the government by messing with elections, well, of course, but I mean for academic purposes. How do you really know who I am? I googled myself the other day—I’m curious how my most recent book is doing because I’ve heard nothing from the publisher since it appeared—and noticed that in the “knowledge panel” on Google they had the picture of the wrong person. I guess I’d better verify myself!

The erstwhile academic (aka “independent scholar”) gets invitations via email from Google Scholar to claim their papers. I suppose in an effort to provide competition to Academia.edu, the researcher finds her or his papers available on Google Scholar’s website. So far, so good. But the invitation comes with instructions to verify your “work email.” Said email must end in a .edu extension in order to be valid. In other words, “independent scholar” is an invalid category. This train of logic demonstrates one of the serious problems with high education shrinkage and the industry becoming tighter and tighter with its positions. How do you verify yourself if your email address is the same as any Jane or Joe? You can’t. “Scholar” is limited to those lucky enough to have picked up a very rare position, especially in some fields, such as religion.

My recent experience with the DMV was an exercise in validation. I presented the woman my vital paperwork (which was less than I had to show to get the New Jersey license that I had to cash in to get a license in Pennsylvania) while wearing a mask. Irony can be quite stunning at times. How did they know I wasn’t some masked bandit stealing someone’s paperwork on the way to the DMV? I guess they could ask me to verify by my work email. Then they’d discover that I’m merely an independent scholar. If they googled me they’d find the wrong person’s photo on my knowledge panel. Won’t someone validate me, please? It would be nice to be able to claim my own papers on Google Scholar. But until “independent scholar” becomes a real thing, I guess you can ask that guy (who’s not me) on the “knowledge panel” that bears my name.