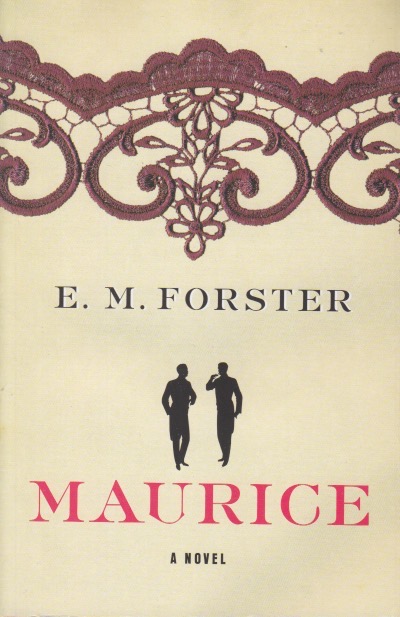

The thing about exploring dark academia is that its recognition is fairly new. It seems that the “concept” emerged only ten years ago and the longer that it’s around the more sources it gathers, like a dust bunny growing under the bed. I’ve never read E. M. Forster before, although I’ve seen movies based on his novels. He was an interesting chap, trying out sci-fi (or at least dystopian fiction) as well as his literary novels. Maurice was not published during his life because it explored homosexuality. Forster was gay when it was technically illegal, and this novel reveals much of the struggle faced by homosexuals during the early decades of the twentieth century. The novel has been cited as an example of dark academia, I suspect because much of the early part takes place in Cambridge. Although it has a happy ending it’s not an easy novel to read.

Quite apart from the hideous paranoia of society at the time towards any kind of homosexuality, Forster’s style was, for me, difficult to decipher. I know this is my issue, and not his. His use of British expressions underscored for me how difficult it is to understand idiom in another culture. At more than one place I was unsure what the speaker meant because the British slang used was so different from what I encountered living in the UK in the early nineties. Not that the story is difficult to follow. It is movingly written, demonstrating the torment of those who realized their orientation as they faced in an intolerant society. Maurice even tries to “cure” his homosexuality, but efforts fail. There is a darkness here, appropriate for dark academia.

Forster died in 1970, just when homosexuality was beginning to be understood not as a sickness, but a disposition. It’s not a choice, and as the animal kingdom tells us, it’s certainly not limited to human beings. The novel makes note of the fact that Greece, the origin of much of western culture, approved and promoted homosexual relationships. Maurice is told that he could move to France of Italy where such relationships were not illegal. There’s no question that the societal stance toward homosexuality was based on particular understandings of biblical texts, some now thoroughly discredited by biblical scholars (Sodom was not destroyed for homosexuality as biblical intertexts clearly show). Generations of people, including Forster, were put through lives of torment in order to keep a prejudice alive. Academia may be dark indeed.