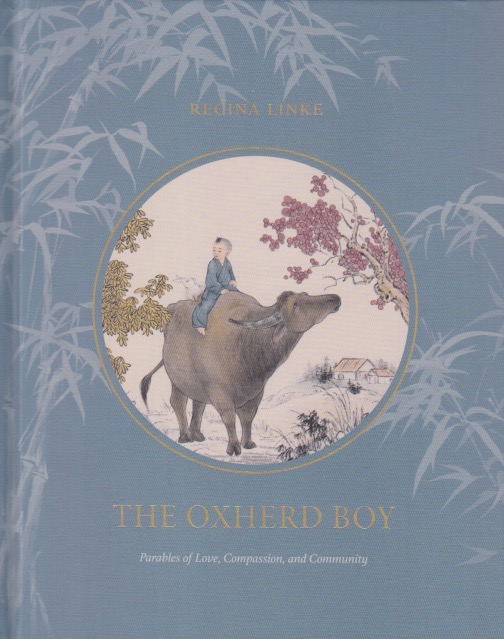

There are some books, such as Trina Paulus’s Hope for the Flowers, or Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, that are inherently hopeful and that you like to have around. Especially in the coming four years full of hate-filled rhetoric. My wife asked for Regina Linke’s The Oxherd Boy: Parables of Love, Compassion, and Community, for Christmas. Of course, I read it too. It is yet another to add to this hopeful shelf. The thing about these three books is that you could easily read them all in an unrushed afternoon. All three are profoundly hopeful outlooks on life. I would recommend having them at hand. The Oxherd Boy is a combination of beautiful artwork with bits of wisdom drawn from Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism that can keep you centered in difficult times.

There’s no real storyline here, but rather reflections. “Eastern wisdom” is kind of a tired trope, but the “religions” of that part of the world can infuse a bit of sanity into many of the facades western religions throw up. I’m not anti-Christian; I fear our society is. It has taken one of these facades and claimed the name “Christian” so that it can get its hate on and feel righteous doing so. There are seldom positive benefits when politics finds religion. If any. The Oxherd Boy reminds us to look for the good in simple things. A life with friends and one in which love is the primary outlook. I believe Christianity began that way, but it became politicized in under four centuries and politics tend to engender hatred. A truly Christian state, through and through, has never, ever existed. And it’s not coming here.

We know hate mongering will take the norm. In fact, while out driving recently I noticed an increase in rude and angry behavior on the part of not a few drivers. There was a noticeable uptick in such behavior shortly after Trump’s first election. In a nation of people that imitate what they see on the media, I suggest staying inside and reading a book. I would recommend The Oxherd Boy among them. As long as you’re stocking up, don’t forget Hope for the Flowers and The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse as well. Books don’t need to be written by academics to try to make the world a better place. In fact, sometimes I wonder about the choices I’ve made. So I’ll pull down the books that give me hope, and reflect.