One of my first publications was a letter to the editor. The newspaper was The Scotsman, Edinburgh’s daily. We’d been hearing on the BBC that a new movie, The Silence of the Lambs, had inspired Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer in his gruesome habit of cannibalism. For whatever reason, the Dahmer case had a real fascination for the British. My letter, a rather young attempt to promote an important cause, suggested that such movies could be very dangerous. In the many years since then I’ve read quite a bit about horror films and their effects on people and have come to the conclusion that they don’t cause the crimes. The reasons are much more complex than simply watching a movie since most people who see them don’t “go and do likewise.” When I told friends in Edinburgh that I’d found a teaching job in Wisconsin they said “hopefully not near where that cannibal lived.” Of course Nashotah House is not far from Milwaukee.

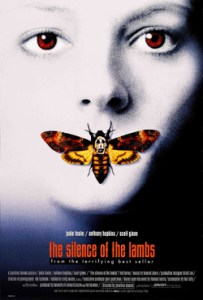

My personal embargo of The Silence of the Lambs ran up against my current research project, which involves horror movies. Thinking it over in what I hope is a rational way, I decided that I needed to see my bête noire. Besides, while living in Wisconsin I had learned about Ed Gein, the local serial killer who’d inspired Psycho, a movie I had seen with no ill effects while in college. Movies are as much a part of life as cars and taxes and all kinds of things that impact our ways of thinking. I was surprised at how well done Silence is and the number of references it had spawned that I had missed for the past couple of decades. It won’t be my favorite film, but I’m not afraid of it any more.

The concept of relying on a criminal to catch a criminal is a classic theme, of course. And since the release of this movie some which are much worse have come across the silver screen. We play our anxieties out for all to see. Hannibal Lecter, the cultured killer, is an ambivalent character—a savior criminal. There’s a strange comfort in knowing he has the knowledge to save lives as much as he has the desire to take them. In fact, there’s an element of the divine in that. The capricious nature of a power that has the ability to give and to take is one with which religions constantly deal. Yes, The Silence of the Lambs is a scary movie. The reasons, however, lie more with implications than with imitations.