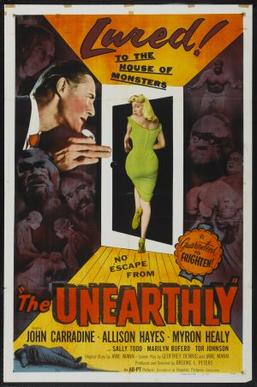

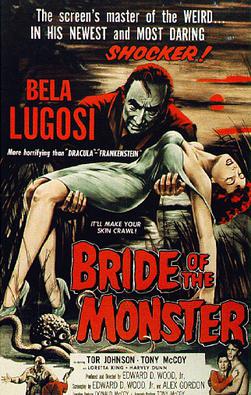

Tor Johnson—actually Karl Erik Tore Johansson—became famous but not rich. Such was the fate of some early horror actors, including Bela Lugosi. Johnson hung out, however, with the low-budget crowd, making the most of his size to take on a kind of “enforcer” role. One of his recurring characters was “Lobo.” Lobo served mad scientists and had very little of his own brain power. He often had few, or no lines to learn. Having watched The Beast of Yucca Flats, in which he starred, I decided to see if The Unearthly was any better. The production values were certainly higher, but this was an earlier film by a different crew. It’s more like the standard fare you expect for a late fifties horror show. It features a mad scientist, and Lobo is, of course, the servant.

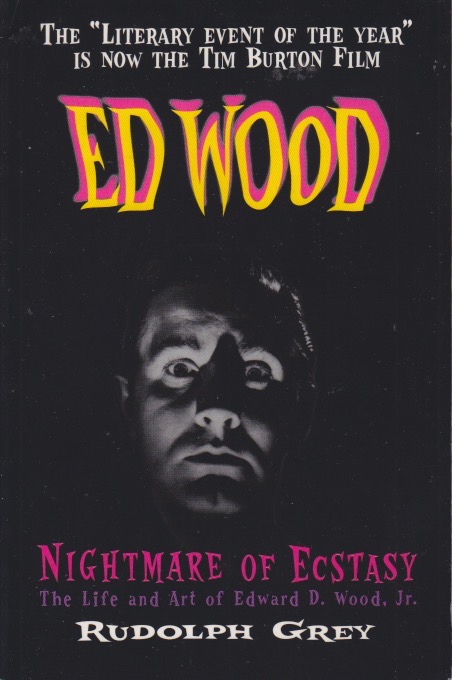

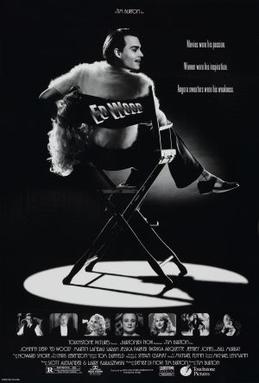

Dr. Charles Conway believes he has found the way to eternal life. It’s attained by transplanting a new gland into a human being. The problem is, it hasn’t worked so far. Like a true mad scientist, Conway is convinced that it will work, it’s just a matter of try, try again. And why advertise for willing subjects when you can have a local crooked doctor send you patients with various personality disorders, and no families, so that you can experiment on them? With slow-moving Lobo as his only security system, Conway carries on until a sting operation catches him red-handed. There’s really not much to this story. It doesn’t have the inspired inanity of an Ed Wood production, but then, it hasn’t really grown a cult following.

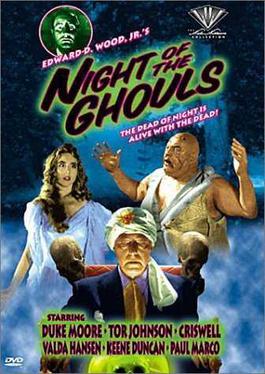

My reason for watching was Tor Johnson. Before I was born he’d attained the status of the model of a best-selling Halloween mask, based on his monster roles. This seems to indicate that his oeuvre was well known, despite the kinds of movies he was in. A large man who’d aged out of “professional wrestling,” Johnson had many uncredited movie roles before hooking up with Ed Wood. He was featured in three of Wood’s films, including the infamous Plan 9 from Outer Space. He’s part of a crowd surrounding the under-funded, independent filmmakers of an intriguing era before modern horror really came into its own. The Unearthly, where his famous line “Time for go to bed” is spoken, suffers from banality and has become pretty obscure. I personally wouldn’t have known to look for it had it not been for the fact that Johnson was in it, dragging it into the “must watch” category. And that it was a freebie.