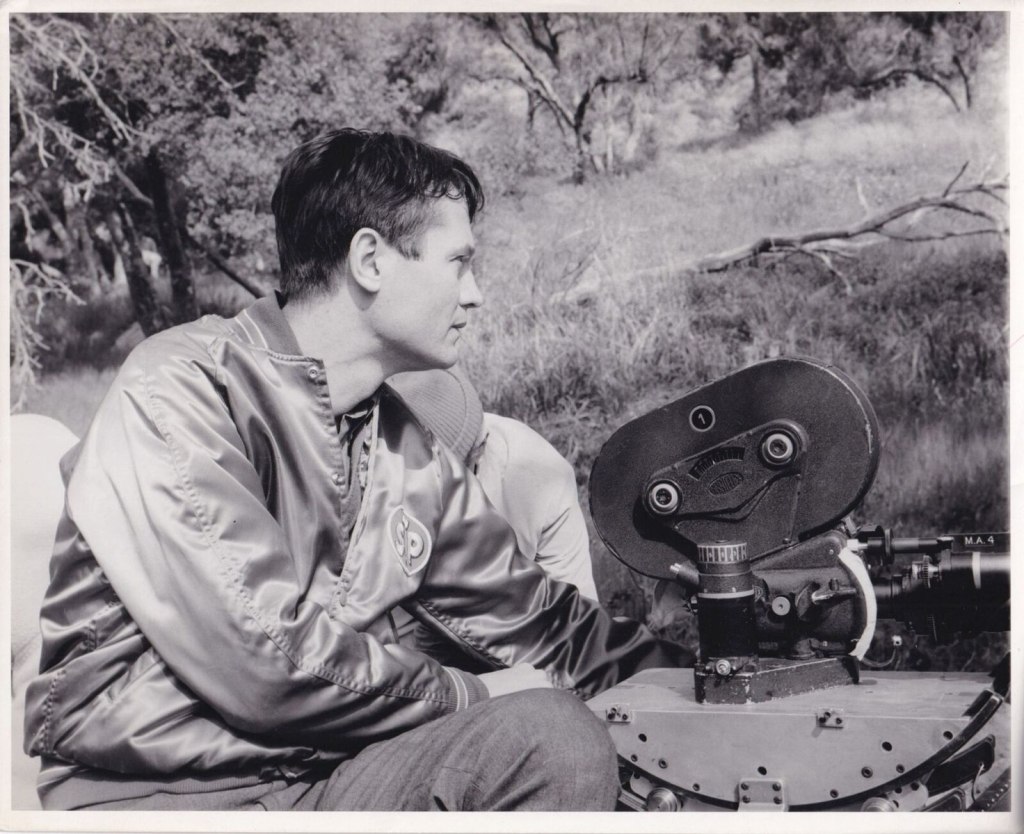

Roger Corman has died. So passes an era. I’ve always had an appreciation for the speculative films of the fifties and sixties. Many of these involved low budgets and content intended to shock. Or at least excite youngsters. And Roger Corman was a huge name among directors, producers, and promoters of such schlock. He entered the realm of horror in 1955 with Day the World Ended. Attack of the Crab Monsters a couple years later put the focus firmly on monsters. Producing and directing three or more movies a year, he built a reputation for being cheap and quick, but that didn’t prevent him from creating some good movies. A film’s producer is the one responsible for overseeing the production. Often they come up with the ideas of what to film.

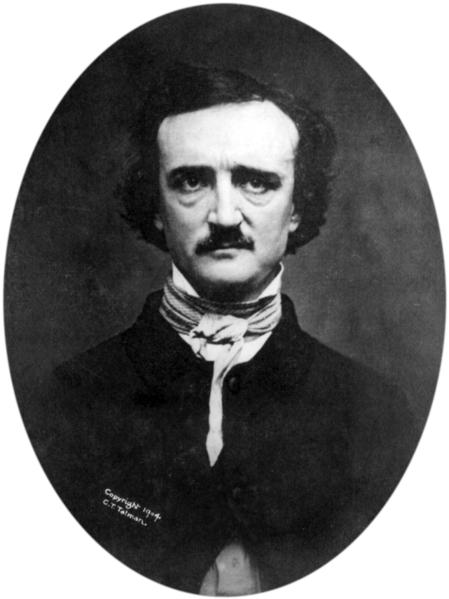

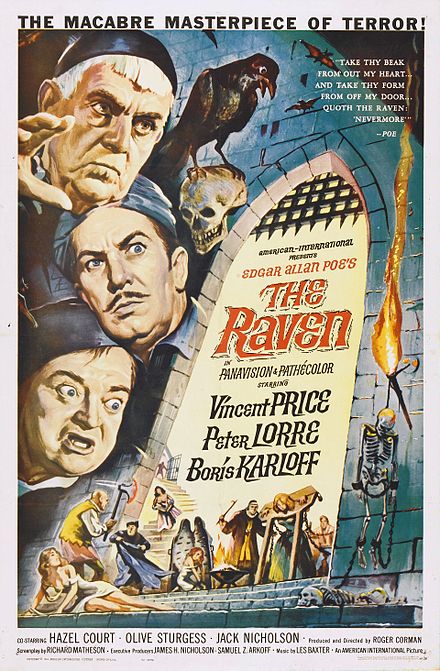

As the sixties were dawning, Corman produced several films “based on” work by Edgar Allan Poe. I remember seeing some as a young person and wondering what they had to do with the Poe I’d been reading. Still, he managed to grace cinema with House of Usher and The Masque of the Red Death. These are good films, despite limitations. At the same time, Corman was still producing creature features as well, wracking up an impressive list of nearly 400 produced films. As an established player in cinema he also took on the role of distributor from time to time. When The Wicker Man was being ignored in Britain, Corman undertook the role of US distributor, likely saving the movie from total obscurity.

Circling back to Day the World Ended, we’ve become accustomed to believe that some kind of divine or human ending is in the offing. These ideas get embellished over time, as I suggested in my new piece on Horror Homeroom. Corman knew that this putative end would get the attention, whether or not there was any truth to it. Perhaps that was the genius of his work—he knew how to attract attention. And he wasn’t afraid to do so. The business of cinema is one of attracting viewers. Telling stories we want to hear. We remember reading Poe, and even if the movies differ from the stories he penned, they are nevertheless reminders, reminiscent of what we’ve read. If there are monsters they are somehow perhaps even more effective for not really being believable. In short, Corman was a showman. He made a living doing what he loved. And he influenced many lives along the way.