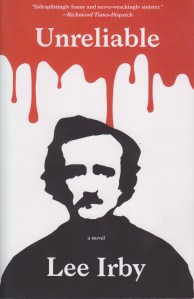

As America becomes scarier and scarier, I appreciate the fact that I grew up loving Halloween. I don’t know why the dark mood appeals to me—I don’t like being scared, and I certainly don’t want others to suffer. It’s more the mood that appeals; think of it as Halloween in the abstract. I begin to feel it in August when I walk into stores already beginning to stock their black and orange wares. It grows stronger through September as the dark comes on noticeably earlier each day, culminating after an October of anticipation. Unlike some consumers of horror, what I’m after is the mood. I started reading Poe as a young person, and “The Fall of the House of Usher” remains my favorite short story. It’s the mood. The narrator riding his horse through the woods toward dereliction. There’s a sublimity in it that’s hard to match.

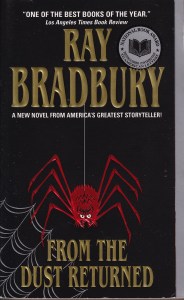

Yes, I watch contemporary horror. I even write books about it. Still, it’s difficult finding others who share my sensibility concerning horror. I don’t like the jump scares or the gore. I’m after the mood. Poe knew about mood—he wrote stories that maintained it throughout. A kind of beautiful hopelessness. It’s a feeling in the air around Halloween when it’s clear nothing is going to stop the leaves from falling and the onset of a long and lonely winter. Writers will shiver in their garrets, allowing their thoughts to flow despite the pale sky and feeble sun that is the only hope of continued life on this isolated planet. Halloween tells us there is a spirit world no matter what the scientific authorities say. It’s a world you can feel, but you can’t find it rationally.

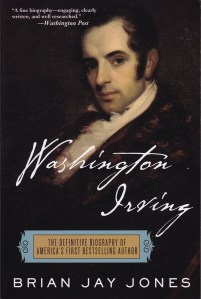

Masquerading is a theme in some of Poe’s work as well. We, as social beings, tend to excel at it. We hide our real feelings so that others won’t hurt us, or so as not to hurt them. We all know the childhood feeling of putting on that Halloween mask that permits us to act as we really feel, within limits. Even as a Fundamentalist, I knew the catharsis of masquerading. I read Poe and I understood him in my own way. As an Episcopalian, I saw how fear of death was hidden behind All Saints and All Souls. Masquerading. Halloween was the Eve of All Hallows, but it usurped the master in its own form of beautiful dereliction. The holidays following this are more comforting and heimlich, until the solstice comes to remind us that light will return, no matter how feeble at first. We need Halloween.