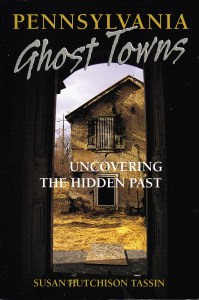

How do you come to where you spend your life? It could be where you’re born. I was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania. Neither of my parents were. On my mother’s side we had a tradition of wandering. We eventually moved to Rouseville, a refinery town not too many miles from where I grew up initially, but very different in character. I knew I wanted to get away. I lived in Grove City next, only as a student. For a short while I resided with some friends in the South Hills of Pittsburgh before moving to Boston to attend seminary. Like many who go to Boston for school, I wanted to settle there. I did so for about a year after graduation, making a living, such as it was, selling cameras. My next move was precipitated by love. I moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan to be with my fiancée, but I’d already been accepted to Edinburgh University, so an international move was imminent.

Edinburgh, like Boston, is a spiderweb. We would’ve stayed if we legally could have, but with a job market for academics already tanking, we headed back over the Atlantic. My wife was a grad student at the University of Illinois, so we moved first to Tuscola (family there), then Savoy (on the outskirts of Champagne-Urbana). Meanwhile I commuted to Delafield, Wisconsin, home of Nashotah House. We eventually moved to Delafield and stayed until I was no longer wanted. Our move to Oconomowoc was necessary to keep our daughter in the same school. The possibility of full-time employment drew me to Somerville, New Jersey. We would stay there until my daughter had a chance to graduate. Depression convinced me that I’d run out the clock in that apartment, but a financial advisor suggested Pennsylvania, where I was born. Thus we ended up in the Lehigh Valley.

I’ve liked every place I’ve lived. If I had my druthers, however, I would’ve ended up teaching at a small college in Maine. Several friends have moved to Maine as I’ve jealously watched. The places we spend our lives, at least in my case, are determined by a measure of fate. Nashotah House was the only job I was offered from Edinburgh. Gorgias Press was the only job I was offered after the seminary. Moving to my home state was volitional, of course. As a couple we’d have been content in Massachusetts, Michigan, Wisconsin, or New Jersey. Economics, of course, has a heavy hand in all of this. I sometimes think that, if I could ever retire, moving to Franklin again would be a way of coming full circle. But then, life is change and we end up, it seems, where we’re meant to be. Perhaps Canada?