While joking around recently with my daughter, I started counting to ten in Spanish. I’ve never studied the language, but I can stumble through academic articles in it with a dictionary. In a senior moment I forgot that “ten” was “diez.” We had a laugh about it and got back to life. The next day while doing my sit-ups, I was counting in German, as is my habit. (The push-ups get counted in English, thank you.) It struck me that “dreizehn” is where the “teens” start, and I wondered if this was because of some base-six counting. I decided to check Spanish to see if the pattern holds. Those of you who know Spanish know that it doesn’t. In English, which follows German, our teens begin at “thirt” (third).

Numbers have always fascinated me. Math not so much. While I find the base-ten system natural, there is something to be said for base-six. I’m not sure if that’s where German “zwölfe” comes from, but it does give us our “twelve.” But those teens are always difficult, aren’t they? In human life we hit sexual maturity with all of its complications. Do we project those onto our numbers? Do other animals do the same? We now know that some animals have at least the concept of absolute numbers down. Some birds know exactly how many eggs are in their nests, and bees know what “zero” means. Their lives tend to be shorter than ours. Do their ideas of numbers reflect that?

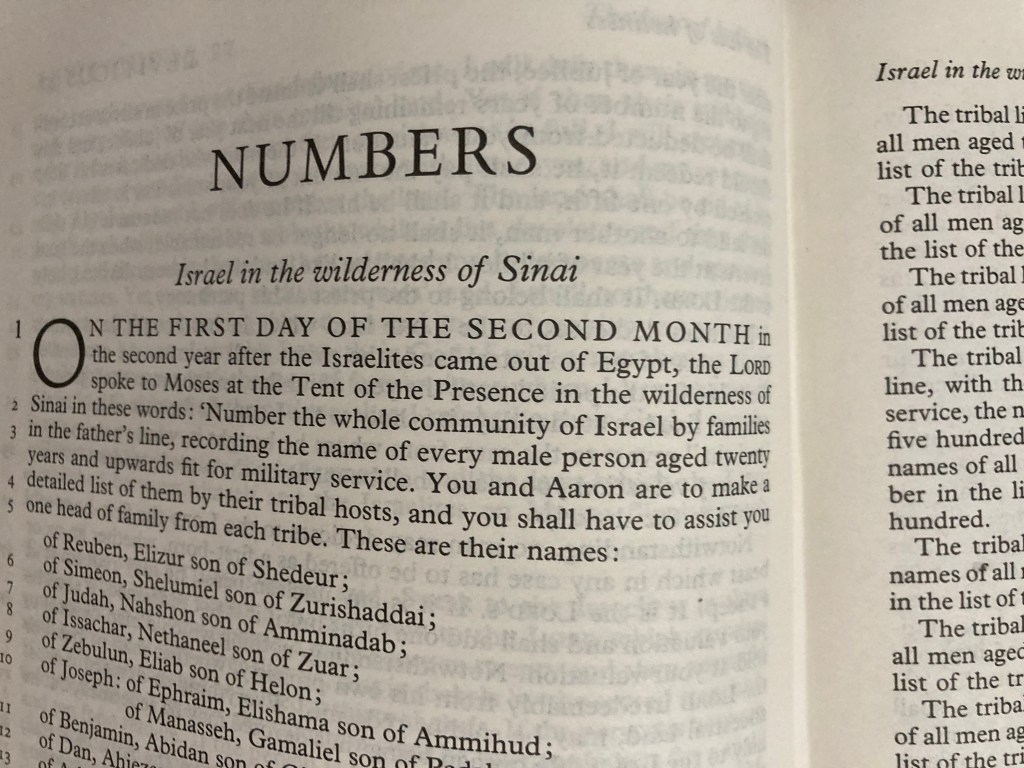

As human beings we know that that good old base-ten number 100 is kind of a life goal. We know that 100 is “old age,” but we know that it isn’t exactly unusual for a person to live that long. Of course “ninety” is compatible with either base-six or base-ten, and is a more reasonable goal. Numbers are used for marking. They’re so basic to our everyday life that, unless you’re a mathematician, accountant, or scientist, we hardly think about them at all. Civilization began, however, with gods and numbers. Kings wanted to know how many people they controlled (some things never change). In the Bible God punishes David for trying to find out. There’s even a book called Numbers. The Mesopotamians used a base-six system that gave us the 360-degree circle. We still use it even though a 1000-degree circle would give us much greater precision. I could muse about numbers and counting systems all day, but it’s time to go do some sit-ups, in German.