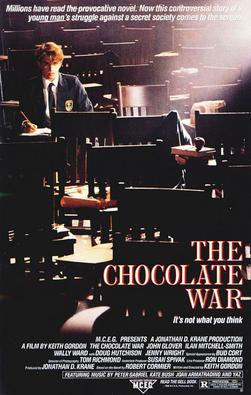

It’s really a teen movie, The Chocolate War is. That may be the sweet spot for dark academia. I’m maybe a bit old for such things, but being old tends to mean remembering how it was. Not exactly how it was, though. Chocolate War takes place in a Catholic boys school, Trinity by name. Perpetually underfunded, the students have to sell chocolate (now we’re in territory I recall—remember me, Gertrude?) to help keep it running. Meanwhile, the Vigils, a secret society, have a considerable amount of pull on campus. Led by a prescient and overly mature boy for his age, Archie, the Vigils assign select students difficult tasks in a kind of high school hazing. Jerry, a freshman whose mother recently died, is assigned to refuse to sell chocolates for ten days. He then decides (for reasons never explained) not to sell them at all.

The refusal leads to a financial crisis for the school. The Vigils try to force Jerry to sell, engaging in harassment tactics. Nothing works. Then Archie coerces him into a “boxing” assembly where students pay to have their specific punches thrown by one of the boys (a bully or Jerry) at the other, who simply has to take it. Before the match begins, Archie, the Vigils’ leader, is tricked into taking the bully’s place. Jerry, who’s on the football team, knocks him out, sending some teeth flying (probably why the film got an R rating). In the end, Archie is demoted, but Jerry realizes that with his refusal to comply, he led to the result he was protesting against (the harassment and boxing match led to selling all the chocolate despite his refusal to participate).

Dated, yes (1988), Dead Poets Society, no. Still, there’s much to ponder here. Bullying—used by very high offices in this land—seems to be a growing problem. And yes, when you get a bunch of adolescent boys together, trouble can arise. It’s believable. Although considered a flop, critics were kinder than the box office. There are dark messages to decode here. The price of nonconformity—an issue that doesn’t disappear with adulthood—and, perhaps looming larger, its effectiveness. The teacher temporarily running the school, Brother Leon, is part of the problem, as is often the case in dark academia. He’s not evil, however. The film places the abuse of power on Archie, although he doesn’t condone violence. Ultimately violence is used to unseat him. With the result that the system (Trinity) prevails nonetheless. Worth considering.