I could blame this week’s Time magazine for declaring that one thing we don’t need to worry about is an end to the zombie craze, but in truth I really have no one to blame but myself. Having watched White Zombie a few weeks back, I decided to see Revolt of the Zombies, its sequel, this weekend. With holes in the plot large enough for a small planet to pass through, it leaves a great deal of creativity – and imagined continuity – up to the viewer. It’s a movie bad enough to make you want to slap the television in frustration, but it did bring a number of my standard (read “tired”) themes on this blog together.

In this confused romp through sci-fi horror, excused only leniently for having been filmed in 1936, the terms robot, zombie, and automaton are used interchangeably. This is one of the technically redeeming features of the film. The term “robot” was coined to indicate a mindless servant, and in their religious origins zombies shared exactly that function of the automaton. Today’s robots are machines, and the future of the Singularity (posted on a couple weeks back) revolves around this very point: machines will complete the degenerating biological frame. Somehow the zombies will save us.

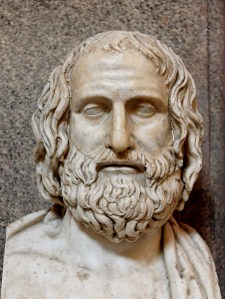

The zombies of 1936 were surrounded by swaggering, stereotyped caricatures of the helpless female who has very little mind of her own (perhaps less than the zombies who actually do something to better their state). Racist images including a wizened Scot called MacDonald and subservient Asians make the film uncomfortable for present day viewers. One glimmer of intelligence in the film, however, comes from an awareness of the classics. After a rat’s nest of a plot that is essentially one man wanting another man’s girl, old MacDonald gives a commentary on the assassinated master of the zombies. He takes his line from Euripides’ play Medea – an original strong female that the Greeks so feared. “He whom the gods destroy, first they make mad.” Second, I would add, they make watch Revolt of the Zombies.