Horror season is upon us. One could argue that it never left since summer has its fair share of horror when air conditioning is required. The one horror director my wife seems to like, apart from the departed Alfred Hitchcock (and some would say he’s thriller, not horror), is Robert Eggers. Eggers’ breakout The Witch worked on so many levels, even for non-horror fans. The attention to historical detail and the solemnity of his approach and the slow build all helped. The Lighthouse was moody and profound, with superb acting throughout. The Northman, his viking epic shot in Iceland, is due out next year. Rumor has it that his fourth film will be Nosferatu. Anya Taylor-Joy, it is said, will be returning for it.

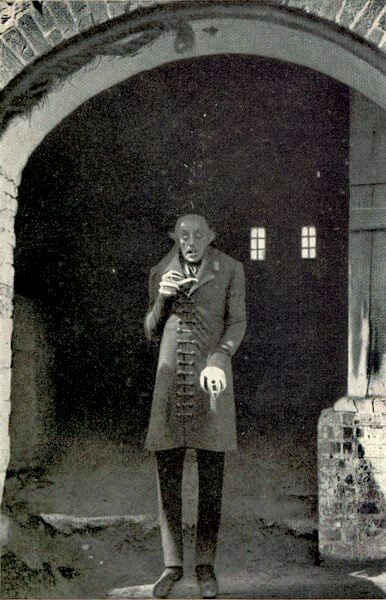

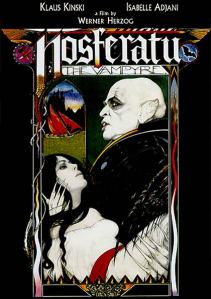

Nosferatu has, as of next year, a century of credibility. F. W. Murnau’s classic, released in 1922, was technically a violation of copyright and was very nearly lost as copies were ordered destroyed. This now iconic film, despite its subtitle A Symphony of Horror (eine Symphonie des Grauens), appeared before the category of “horror film” was assigned, and so it’s normally not considered as part of the genre. The original was given a shot in the arm by Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre in 1979. My long-suffering wife once agreed to watch it with me. There are parts of the movie that are distinctly disturbing, but it remains one of the best vampire films ever made. Many would classify it as an art film more than a horror film, just as Murnau’s was considered Expressionism rather than horror.

It remains to see how Eggers will handle this script. The original plot was based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, one of the formative novels of the western canon. The story of an unassuming individual unexpectedly encountering, through a small conspiracy (in the films), the supernatural. That which we’re all told is not really there. Many are beginning to wake, after the election of Trump revealed that evil does really exist, to the understanding that not all is as it seems. It’s hard not to sympathize with the vampire in the movies, particularly when he’s the victim of a curse. A vampire’s got to eat, right? The original, of course, made him out as a devil. That was in the days when selfish bloodsucking was considered evil, not business as usual. We have a lot to learn from vampires, and I, for one, am eager to see how Eggers will handle Nosferatu.