It’s difficult to tell where summer begins and spring ends. Transitions are like that. Today’s the summer solstice. Since I’m an early riser I keep track of when the sun comes up so that I can go for a jog. Actually, I tend to get out just before sunrise when twilight is enough to see by. You see, the solstice is a day of hope. My jogging path is on the edge of town and it borders some woods that, all things considered, are quite shallow. There’s development on the other side of the river, although you can’t see it from here. As I’m out before most other crepuscular exercisers I often see critters along the trail. I’m not sure I can catalogue all the animals I’ve seen but a partial list includes fox, coyote, raccoon, bald eagle, raven, ducks, herons, and the ubiquitous rabbits, squirrels, and deer. Last month I saw a doe giving birth as I jogged by, something I felt it inappropriate to watch beyond a passing glance.

At times when it’s too dark to go before work I have occasionally gone on a slightly later schedule. Then I’ve seen groundhogs, a snapping turtle, and red efts (newts). The thing is these woods are rather thin and they support (along with the towns, I’m sure) a variety of creatures, many of which I don’t see. Appearances can be deceptive. Things that appear certain are often wrong. Those who wake later and don’t spend their evenings on the trail (and animals, I expect, are shy after people have been out all day) may not believe there is so much fauna in the area. I know there’s even more: opossum, bear, and frogs among them. I believe they are there. And believing is just as important as knowing.

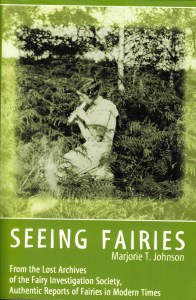

Summer is thought of as a more relaxed time, but that’s really only an appearance as well. It’s actually quite a busy time—what’s relaxed is our capitalistic drive for work. We realize the warmer days (hopefully not too rainy) afford us the opportunity to do the things the long, dark, cold months prevent. And those of us in northern latitudes tend to think of it as a magical time. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream captures the traditions of fairy activity during this short night with long, sunny days either side of it. A family member recently reminded me of this connection, and it seems to me that we should be reminded once in a while of the miracles that surround us. The solstice is one of them. It’s a matter of believing and a cause for hope.