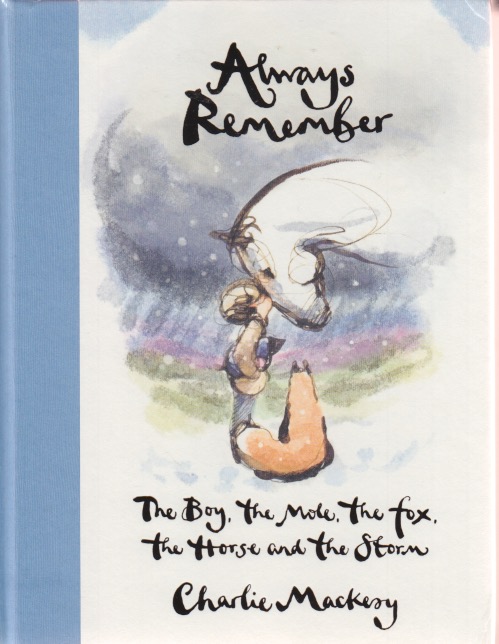

Books used to be, and often still are, works of art. I can’t imagine my life without them. I read Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse back in 2023. A psychiatrist that’s a friend of mine recommended it. Mackesy’s next book of wisdom, Always Remember: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, the Horse and the Storm just came out in 2025. It was a stormy year and I can’t help but think this book was one of the antidotes that the world seems to hide next to the poisons it contains. The book is a work of art. Like its predecessor, it builds on the importance of love, friendship, and hope. These are the kinds of things we need in difficult times. Indeed, we are in the midst of a four year storm that threatens to tear apart 250 years of progress. We need this book.

I wanted to save this book to be the first I finished in 2026. To start the year off in a good way. I’m not a maker of resolutions since I try to self-correct as soon as I become aware of a problem. But reading a positive book at the start of the year seems like something that is smart to do. It’s so easy to get drawn into negativity. Doomscrolling invites itself to be shared with others. Pretty soon we’re all mired down. But the horse is fond of reminding the boy, mole, and fox, “The blue sky above never leaves.” It is there waiting for us, after our self-inflicted storm ends. As I’ve noted before, writing books is a hopeful exercise. Reading them can be too.

Charlie Mackesy is my age. He seems to have distilled more wisdom from our time on this planet than I have. Reading his observations is the very definition of nepenthe. When the headlines foreground hate, we must respond with love. When everyone tells us the storm will never end, we must beg to disagree. Humans are problematic creatures. We create our own ills much of the time. There are those among us, however, who are wise. And we can improve our state if we choose to listen to them instead of those who loudly proclaim their own praises. Wisdom is often in short supply in this world we’ve created for ourselves. It is not, however, completely absent. Do yourself a favor and find Always Remember. No need to save it for a rainy day.