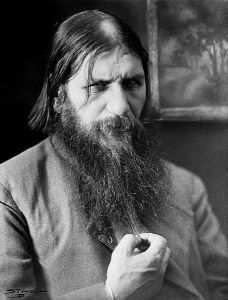

What could Aimee Semple McPherson have in common with the devious Russian monk Rasputin? Apart from being contemporaries for a couple decades, they were both faith healers. Well documented cases exist for both of them, and the medical profession has started to come around to the idea that belief can, and does, heal. The stories of Sister Aimee’s healings, witnessed by thousands, make me fear being thought gullible just for bringing it up. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Cases exist even today where healing inexplicably takes place before scientific eyes. Often it occurs in response to religious stimulus. We may have proof that it happens, but we tend not to believe. This is a curious state of affairs. We trust in reason to the point that it may prevent us from being healed by faith.

Some object, of course, to the theological element. It’s pretty tricky to believe God has healed you if you don’t believe in God. The thing about faith healing, though, is that it seems to work no matter the religion of the person healed. This, it would seem, suggests we should be applying our rational minds to understanding belief. Instead we use it to find new ways to make money or to build smarter weapons to kill one another more efficiently. The more we come to understand the physical world around us, the less we know. As our research institutions take on the shape of the businesses that increasingly fund them, interest in this phenomenon shrinks. Medicine, in all its forms, is big money. Living in central New Jersey you can’t help but notice the palatial campuses of the pharmaceutical companies, nor ignore the mansions on the hill they have built. If only we could believe.

Faith healing was this aspect of her ministry that propelled Sister Aimee to fame. She constantly underplayed it, not wanting to be considered a healer of bodies so much as a healer of souls. Rasputin, of course, had political motives. Both lived—not so long ago—when faith was taken very seriously. Judging from the posturing around the least religious president in decades, whatever faith is left has been sorely effaced. Maybe it’s our minds that have the capacity to heal, but even that well seems to have been drained with the leaky bucket of rhetoric. History can teach us so much, if we’re willing to invest in it. How does faith healing work? I have no idea. Nor, it seems, does anybody else. So it will remain until it becomes commodified.