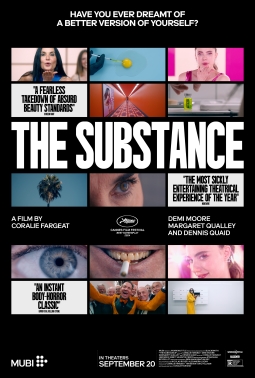

Body horror isn’t my favorite, but The Substance was so widely acclaimed that I figured I needed to see it. It’s easy to see why it was so well received—it is not only well done, it also packs a lot of social commentary into the story. I hadn’t read about the plot before seeing it, and it occurred to me that the theme wasn’t dissimilar from Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson,” but from the point of view of a woman who’s been celebrated for her good looks and finds herself aging out. Elisabeth Sparkle has had a successful television personal fitness series for years. When she turns fifty, however, studio executives decide she has to be replaced with someone younger. The men in the movie are portrayed in an unflattering light, unable to curb their appetites, while Elisabeth has to stay in shape, remain “beautiful,” to find any work at all.

Then a doctor furtively informs her about “the substance.” It comes with few instructions, but it causes a person to create a new version of themselves—younger, more attractive—but they must swap out their existence every week. One week the younger body is active while the older body is comatose and then they keep on switching weekly. The younger Elisabeth, named Sue, takes Sparkle’s job and becomes a hit. Her fitness show, highly sexualized, quickly gains ratings. Sue has boyfriends and glamour. Elisabeth awakes to find the apartment a mess and starts to regret the doubling. The advertising for the substance repeats the message, the two of you are one. Then Sue starts to “stay out late,” taking a few extra hours before switching. This causes Elisabeth to age, in pieces, very rapidly. She takes her revenge on Sue by overeating and leaving the apartment a mess.

Of course this is building to a big finish, which I won’t describe here. There are a number of themes the film asks us to ponder. Women are expected to stay young to be valued by the men who control the money. The divided self comes to hate itself. And there is little recourse for those whose careers reward them richly for being young but who will live well beyond that with only the memories and regrets of what they no longer have. Although the movie is deliberately comic in many respects, it is also a sad story. Expectations are unreasonable and unrealistic, and women have to play by the rules set by men. The Substance has depth and pathos. And pointed social commentary.