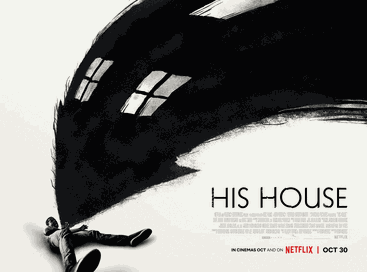

In this season of deportations, thinking about what it means to be a refugee couldn’t be more important. The horror film His House makes you do just that. Bol and Rial are fleeing war-torn South Sudan with their daughter. After a mishap on the overcrowded boat from France to England, their daughter drowns. Kept in a refugee camp for months, they are finally allotted a council house in poor repair and a meager income. If they violate any of the rules, which include living anywhere else or trying to earn their own money, they will be deported. Bol tries to assimilate quickly while Rial is more tied to her traditional ways. Then the ghost of their daughter, and other dead from the war and the crossing, begin to haunt them. All the while they face the threat of deportation. Some spoilers follow.

Rial recognizes the ghosts come from an apeth, a kind of witch that demands repayment for the crossing. Bol sees the ghosts too, but denies it. They will not go back, he insists. When the social workers come to inspect the house, after Bol asks for a different place, Rial tells them a witch is causing the problems, causing the Englishmen to roll their eyes. When Rial tries to escape, an alternative reality back in Africa shows that when Bol was denied a place on the overcrowded refugee bus, he grabs a random girl—their “daughter”—to get a place on board as the soldiers begin shooting. The girl’s mother is left behind, screaming for her child. The apeth is demanding Bol’s life for that of the girl he used to gain his freedom. Rial, realizing that Bol will die for trying to make their life better, attacks the apeth and lets go of the image of their daughter.

This is a sad and thoughtful kind of film. We seldom stop to think that refugees, in culture shock already, are stripped of everything familiar and made to feel as if continuing to live is itself a special favor. They have their own ghosts too. The real horror here comes through seeing the world through the eyes of someone who has experienced a high level of trauma. To do so while Trump’s storm troopers are once again separating families, killing people at will, and deporting refugees, is not an easy thing to do. Horror can be an instructive genre, and although the threat here is supernatural, as it often is in folk-horror, the real fear is all too human.