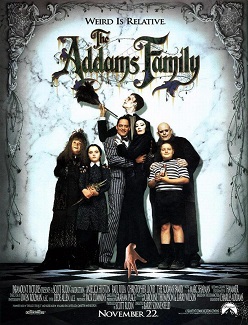

After having binged on Wednesday earlier this year, and wanting something lighter to watch, we finally saw The Addams Family. Neither my wife nor I watched the television series too much when we were kids, but it’s probably no surprise that I watched it more. As with Wednesday, if you didn’t see the television show, or read Charles Addams’ cartoons, you can still enjoy the movie. After all, some of the salient aspects of the eponymous family are never explained. Why are they so wealthy? Things like that. Although the movie, which is family friendly, can’t be called horror, it is a dark humor piece that scratches a certain itch. For several years I’ve been pondering how horror has become such an amorphous genre that it really tells us little about a movie. Taken literally, this one would be horror.

Not having grown up as a particular fan, I never really attempted to research the Addams family, but the basic idea was that they were people who lived as they liked, not caring what others thought of them. They remain happy and cheerful in their macabre tastes. The humor in such a situation is obvious. The ultimate non-conformists, they are wealthy enough not to have to worry about fitting in. Also, they tend to have some supernatural abilities. Watching the show growing up, the character that never seemed to fit the macabre image was Pugsley. Often a partner in crime for Wednesday, his “monstrous” nature seldom seemed obvious to me. Maybe it was his outfit. In any case, not fitting in is what the show is all about. Not fitting in and not worrying about it.

The plot of the movie is surely well known by now. Gomez’s brother Fester is missing and a criminally minded Abigail Craven sends her lookalike son Gordon to take Fester’s place to get access to their riches. The humor, apart from the madcap plot, often comes from subverted expectations. A character points out a gloomy, macabre, or scary situation followed by a comment of how much they enjoy it. As I’ve noted, taken literally such things define horror. Horror and comedy can work well together. In fact, I’ve reviewed many horror comedies on this blog. I would have never thought to have watched this movie, however, without the prompting of Tim Burton’s Wednesday. She’s an underplayed character in the series since the focus tended to be on the bizarre adults, as far as I can recall. As Christina Ricci’s second feature film, her Wednesday laid the groundwork for the Burton series. Maybe it’s time to do a little more research into family history.